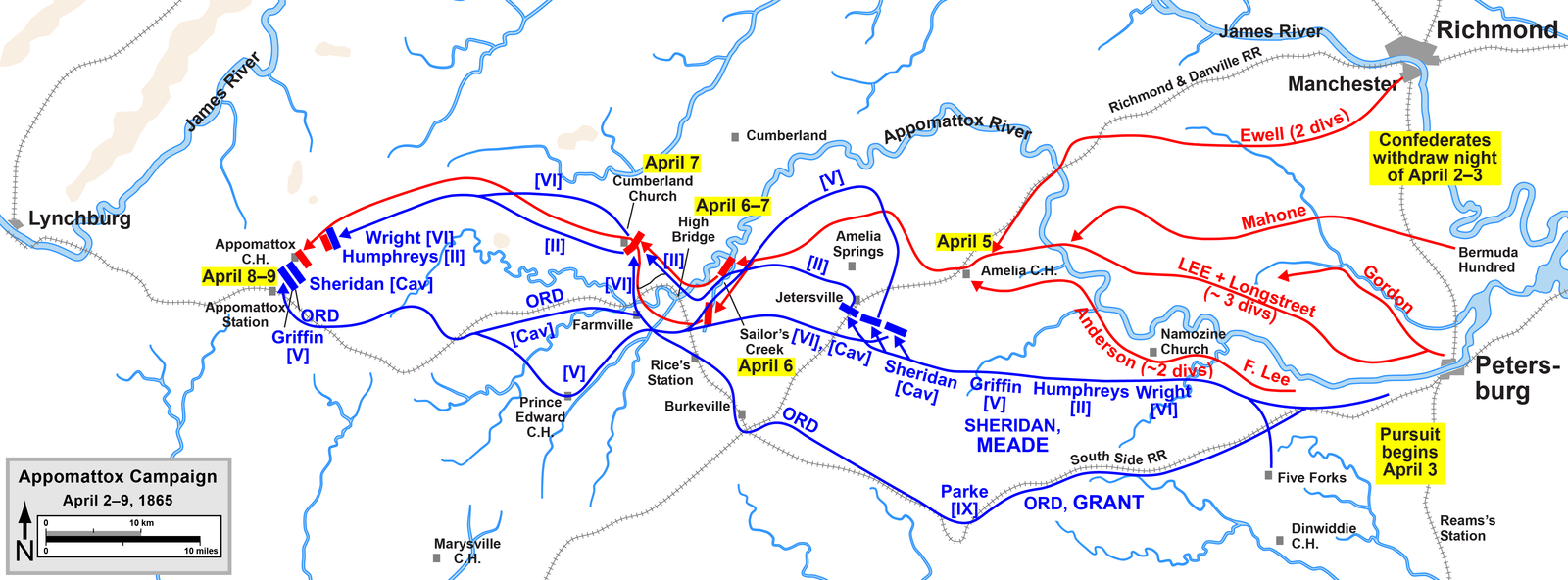

April 2nd - 3rd The Fall of Petersburg

After the success at the Five Forks intersection and the capture of thousands of prisoners, the Union troops struck a final blow on Petersburg. At 4:30 a.m. the VI, IX, and XXIV Corps all struck the thinned Rebel lines from directly south and east of Petersburg. After the failed attack on Fort Sheridan on March 25th, the space between the two armies had narrowed considerably. VI Corps broke through in a very short time. Further east, General Ord’s Army of the James and General Humphreys’ II Corps attacked towards Petersburg and also broke through.

By noon, the Confederate troops were being pushed back on multiple fronts around Petersburg, fighting mostly to delay the Union troops so their comrades could slip away. The President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis and his fellow officials boarded trains on the Danville - Richmond Railroad line to flee south (Davis would escape to Georgia, where he was captured weeks later). General Robert E. Lee and his troops fled west, many going north of the Appomattox River to evade capture.

Back at Five Forks, General Miles’ division from II Corps had come west on White Oak Road before midnight of April 1st as a precaution against a Rebel counterattack. With the Rebels in flight in the morning, at 7:30 a.m. Miles turned around and went back in the other direction.

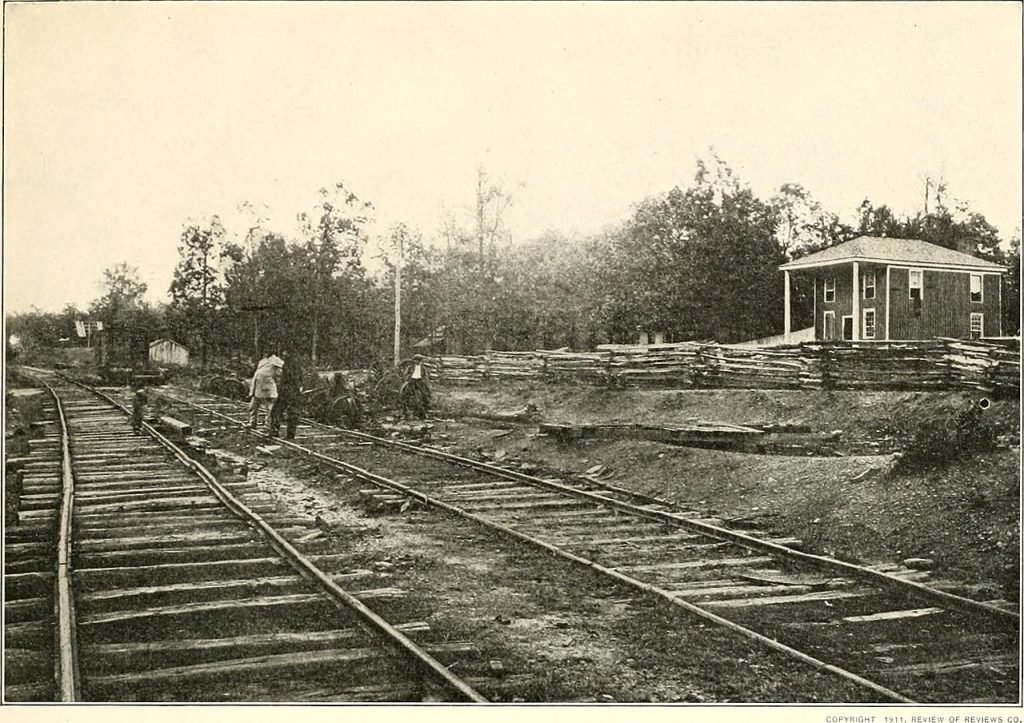

They arrived back at the Claiborne Road intersection on White Oak Road and found it abandoned. So the division pushed up Claiborne Road and reached the Southside Railroad by 3 p.m. where the Rebels had dug in. The ensuing Battle of Sutherland Station would eventually see Miles’ division take the station and General Meade’s headquarters for the Army of the Potomac move up to this area.

V Corps Gets a New Commander

After the battle at Five Forks, General Sheridan had relieved the V Corps Commander, General Warren. Sheridan falsely believed that Warren had moved too slowly on the evening of March 31st and at Five Forks the next day. The charges that the hot-headed Sheridan leveled at Warren were essentially slander, but Warren’s leadership and V Corps’ performance was later vindicated (in a Board of Inquiry that began 14 years later, 1879-82).

The new V Corps commander was now General Griffin from 1st Division. V Corps spent the morning caring for the dead and wounded. They also got food and supplies. In the afternoon, Griffin led the Corps Divisions back down White Oak Road. They were first meant to support II Corps. However, they were later directed to Church Road, where they turned north towards the South Side Railroad lines. From there, Crawford’s 3rd Division (and the 94th NY Infantry) were sent north with to support the Cavalry Corps as they faced fleeing Confederate troops. These Rebels were none other than those of General Fitzhugh Lee, whom the cavalry and V Corps had fought the day before.

The Rebels Take Flight

In the evening, the Rebels who weren’t captured would clear out of Petersburg. General Lee gave orders for the Rebels to retreat to the northwest of Petersburg. They would rendezvous at the Amelia Court House, where they expected to find food and supplies. By the morning of the 3rd, the Union’s attack would break through the last Petersburg defenses. The 9-month-long siege of the city was finally over. Major Evan M. Woodward, of the 198th PA Infantry in V Corps 1st Division, wrote:

“(Jefferson) Davis and his host of satellites fled in confusion and dismay. On our lines for miles the bands pealed forth our national anthems, and soldiers vented their frenzies of delight in loud cheers, until “the musicians fell asleep with their horns to their mouths, and boys waving their caps in the air.” Never in this wide world was there such utter despair and wild rejoicings in armies before.”

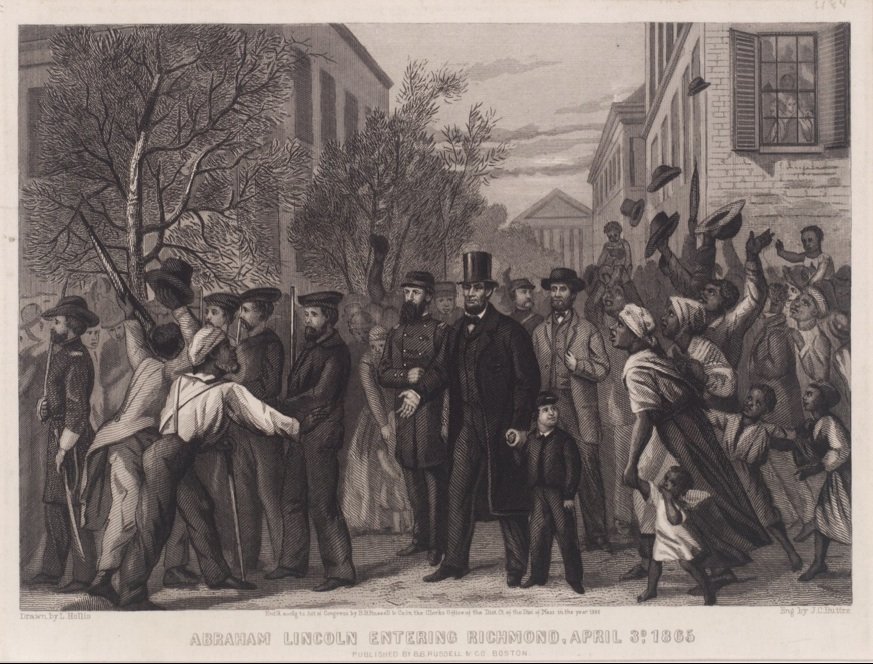

As the Rebels fled Petersburg, they set fire to munitions and equipment they couldn’t carry with them. This started a fire that burned through a large part of the city on April 3rd. At 3 a.m., the Union troops closest to Petersburg entered the city unopposed and secured important locations around town. President Lincoln would enter Petersburg later in the day. On the 4th, he would take a steamer up the James River to Richmond with a handful of guards and aides. There he would be flocked by the now freed former slaves in the city as they celebrated their freedom.

April 4th - 5th: V Corps Pursues Robert E. Lee

With General Lee and his remaining 35,000 troops on the run, the rest of the Union Army Corps took chase. Some units followed the Rebels as they headed west and northwest. Others kept south of the Confederate troops, blocking every road that headed south.

On April 4th, Lee arrived at Amelia Court House, but there was no food for his troops, only ammunition. With his men having gone hungry for the last few days, Lee sent out troops to scour the countryside for food. But the day spent looking for food was a waste of time, as there was little food to be foraged in the area. In the meantime, Union troops had closed in around them.

My great-grandfather’s V Corps spent April 3 - 4 marching nearly 40 miles from Sutherland Station behind the Cavalry Corps. After a full day of marching on the 4th, they blocked the route of the Richmond - Danville rail line at Jetersville, VA. Many Rebel troops had come down the train line from Richmond, disembarking just before the Union’s blocking positions on the lines. With an escape by rail blocked and no food available, Lee and his men moved out west again from Amelia County on the night of the 5th, just missing a Union attack planned for dawn the next day.

April 6th: The Battle of Sailor’s Creek

At 6 a.m. on April 6th the II, V, and VI Corps took up battle formations around Amelia Court House and the surrounding area, hoping to catch General Lee’s forces there. With Lee having escaped, the II and VI Corps followed the trail left by his column, while the V Corps moved north of the Rebels. Further south, the Union’s Cavalry Corps remained close to the rail lines, keeping on a parallel course to the south of the Rebels, to prevent their escape to North Carolina. Major Woodward from V Corps’ 1st Division described the scene of the chase:

“On the first day of the pursuit, an occasional dead man or an empty haversack only marked the track of the enemy’s flight. But these multiplied, intermixed with broken-down wagons, abandoned guns, used-up horses, and the general débris of a fleeing enemy. Nor was the flight confined to the army. The inhabitants, generally, had been led to believe our war was waged against the unarmed and helpless as well as the hosts of Davis and Lee. Men, women and children, with their goods and chattels packed in queer country carts and strange-looking vehicles, were met fleeing in every direction, as if the scourge of God was upon them. Wild with fright, some begged for mercy... Amidst so much distress it was a relief to see the cheerful, hopeful, trusting faces of the slaves, who felt that the day of deliverence from bondage for which they had for generations in secret prayed, had come at last.”

The Union troops caught up with the Rebels three times on the 6th, before and after they crossed Sailor’s Creek. Much of the fighting was done between the Rebels’ rear guard and the lead elements of the Union army. By day’s end, the Union captured 7,700 Confederate soldiers while another 300 were killed or wounded in the fighting.

The senior Confederate officers met on the evening of April 6th and concluded that without food or supplies, surrender may be inevitable. Nevertheless, the armies marched on.

April 7th - 9th: The Finale - Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox Court House

After the clashes at Sailor’s Creek, the last of the war in Virginia followed a similar hit-and-run pattern. The Rebels’ rear guard clashed with the pursuing II and VI Corps at every turn. But General Lee’s army marched on, hoping to reach the South Side Railroad line at Appomattox Station.

Sensing the flagging prospects of the Rebels, General Grant sent General Lee a letter on the 7th, suggesting that the Confederates had little hope left. Lee responded saying that his army still hadn’t lost hope, but he also asked what terms would be offered should he surrender.

April 7, 1865.

“General: I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.”

R. E. Lee, General.

Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps, V Corps, and three divisions of the Army of the James raced west, 10 miles south of the Rebels column. Along the way, freed slaves would provide intelligence on the Rebel retreat. They reported that small groups of Confederate soldiers had been passing through this part of Virginia for 8 or 9 days, likely a mixture of deserters and lead elements of the retreat.

At least the march had brought the V Corps to a more pleasant part of Virginia. Sergeant William Strong, from the 121st Pennsylvania Infantry in Coulter’s 3rd Brigade of 3rd Division, described the scenery they passed on the 6th and 7th:

“The beautiful country and fine farms now beheld were in striking contrast with what had all along been the experience in Virginia. The pretty hills over which the line of march passed, afforded splendid views for miles around, and the prospect, together with the great quantities of bacon, corn meal, poultry, etc., that continually fell into the hands of the men seemed to indicate anything but the starvation among the rebs, of which we had heard so much.”

By April 8th, V Corps had marched over 100 miles in less than a week. The only refreshment gained was wading through the cold creeks they marched through along their way. General Chamberlain, from 1st Division, described their state:

“The Fifth Corps had a very hard march… We had been rushed all day to keep up with the cavalry (though were delayed by the slow-moving XXIV Corps ahead of them)... We did not know that Grant had sent orders for the Fifth Corps to march all night without halting; but it was not necessary for us to know it. After twenty-nine miles of this kind of marching, at the blackest hour of night, human nature called a halt. Dropping by the roadside, right and left, wet or dry, down went the men as in a swoon.”

The column of troops halted after midnight for rest. But a few hours later, the V Corps commanders received word that Sheridan’s cavalry had captured a Confederate supply train at Appomattox Station. It was loaded with food, ammunition, and wagons from the south to refresh and resupply Lee’s starving army. Sheridan urged V Corps ahead to help secure their position. General Chamberlain continues:

“Ah, sleep no more! The startling bugle notes ring out “The General”—"To the march!" Word is sent for the men to take a bite of such as they had for food : the promised rations would not be up till noon, and by that time we should be—where?

You eat and drink at a swallow; mount, and away to get to the head of the column before you sound the “Forward.” They are there—the men: shivering to their senses as if risen out of the earth, but something in them not of it! Now sounds the “ Forward,” for the last time in our long-drawn strife; and they move — these men — sleepless, supperless, breakfastless , sore-footed, stiff-jointed, sense-benumbed, but with flushed faces pressing for the front.”

As dawn broke on April 9th, the Confederate infantry arrived at Appomattox and began pushing Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps back. V Corps and XXIV Corps had continued to move through the night. At 4 a.m., they were 2 miles from the courthouse and pressed ahead.

General Chamberlain’s 1st Battalion from V Corps’ 1st Division pushed to the head of V Corps at the request of Sheridan. Corporal John L. Smith, from the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry in 1st Division, noted a message of urgency was passed through the lines:

A staff officer rode along the column with the word that, if the infantry would “ rush up,” Lee’s capture or capitulation was assured.

At 6 a.m. the lead elements of the 20,000+ man column had reached Sheridan’s headquarters. The soldiers marched ahead and were pressed into lines as they arrived in order, with V Corps’ 1st Division elements arriving first, then General Ord’s XXIV Corps, and finally 2nd and 3rd Division from V Corps. My great-grandfather’s 94th NY Infantry arrived with its 3rd Brigade at 8:30. The Rebels’ escape was effectively blocked.

Shots were fired back and forth during the early morning, with the Rebels holding the more strategic positions on the Appomattox plain. Unbeknownst to the rank-and-file soldiers, Generals Grant and Lee had been exchanging letters throughout the night and into the morning of the 9th. Peace seemed to be near at hand. Then, sometime after 10 a.m., a sole rider appeared before the Union army’s line. General Chamberlain described the scene:

“My right was “in the air,” advanced, unsupported, towards the enemy’s general line, exposed to flank attack by troops I could see in the distance across the stream…"

Suddenly rose to sight another form, close in our own front,—a soldierly young figure, handsomely dressed and mounted, — a Confederate staff-officer undoubtedly, to whom some of my advanced line seemed to be pointing my position. Now I see the white flag earnestly borne, and its possible purport sweeps before my inner vision like a wraith of morning mist. He comes steadily on,—the mysterious form in gray, my mood so whimsically sensitive that I could even smile at the material of the flag,—wondering where in either army was found a towel, and one so white. But it bore a mighty message,—that simple emblem of homely service, wafted hitherward above the dark and crimsomed streams that never can wash themselves away.

The messenger draws near, dismounts; with graceful salutation and hardly suppressed emotion delivers his message: “Sir, I am from General Gordon. General Lee desires a cessation of hostilities until he can hear from General Grant as to the proposed surrender.”

General Grant earlier had proposed a 10 a.m. meeting at the Appomattox Courthouse but, in the delay in passage of letters, Lee did not receive this message until after 10. The message from the Confederate’s General Gordon proposed a cease-fire until 1 p.m. until they could begin talks. Then another rider appeared with a white flag, again with a message, but talking of “unconditional surrender.”

But not everyone got this message at the same time. As General Chamberlain continues:

“Just then a last cannon-shot from the edge of the town plunges through the breast of a gallant and dear young officer in my front line,—Lieutenant Clark, of the 185th New York,—the last man killed in the Army of the Potomac, if not the last in the Appomattox lines.”

General Lee’s final reply to Grant came in just before noon:

“General : I received your letter of this date containing the terms of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia as proposed by you. As they are substantially the same as those expressed in your letter of the 8th instant, they are accepted. I will proceed to designate the proper officers to carry the stipulations into effect.”

R. E. Lee, General.

The last letter from Grant to Lee found Lee lying on a blanket a half-mile from the courthouse. The meeting was set. But to avoid a restart of hostilities, a message was passed from General Meade’s headquarters (that had been chasing Lee from behind) through the Confederate lines to the Cavalry and V Corps commanders on the other side of the valley. At 1:30 p.m., Grant finally arrived at the McLean house and the talks with Lee began.

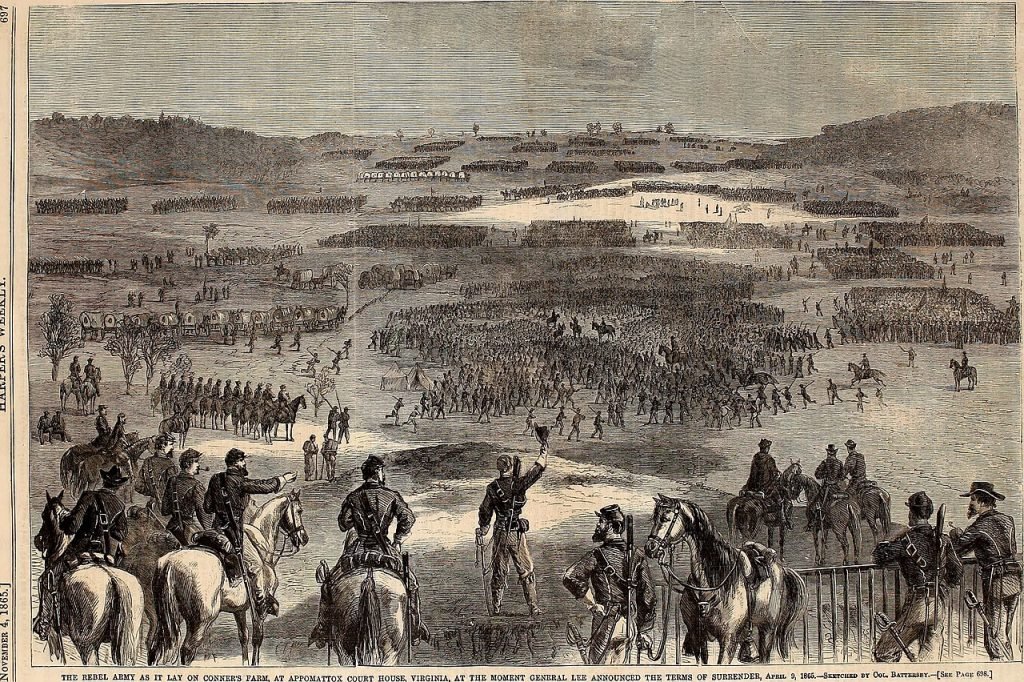

Rather than developing terms of peace, the letters between Generals Grant and Lee had negotiated a surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. The war was not finished, but Robert E. Lee’s army was now out of it (Johnson’s army would surrender in North Carolina 17 days later). The Rebels laid down their arms and other equipment, though officers could keep their side arms and horses. All soldiers and officers were allowed to return home, unmolested by Union troops.

The Generals and Soldiers Meet

And so the fighting in Virginia had stopped. The Union and Confederate generals met near Appomattox Courthouse, at a private home owned by the McLean family. Generals Lee and Grant acknowledged the surrender terms in writing and afterwards Union generals collected whatever mementos could be carried away. Some combatants were old friends from West Point, now reacquainted. Among those in attendance was General Samuel Crawford, commander of V Corps’ 3rd Division. Crawford had been a Union army surgeon at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, when the Rebels first attacked Union troops on April 12, 1861. He was one of a handful of men who saw the war’s beginning and its effective ending at Appomattox Courthouse.

The news of surrender slowly filtered back to V Corps and to my great-grandfather’s 3rd Brigade in the 3rd division. Sergeant Strong of the 121st PA Infantry recalled the moment:

“At twenty minutes to four o’clock, information was received that General Lee had surrendered.

The order was read to the troops stating the conditions of the surrender and the disposition of the prisoners. The joy that pervaded the ranks of the completely tired out veteran patriots knew no bounds. The demonstrations of gladness among the Union troops were really inspiring. The full, round Yankee cheer resounded over the field, and hats, clothing, boots, anything that could be laid hold of, were sent flying through the air, that at times was almost black with these missiles.

These demonstrations although of gladness, were far from those of exultation over a fallen foe, and it appeared to be the universal feeling among the men that their late enemies should not feel the humility of defeat so far as they could prevent it. As opportunity occurred the men in blue mingled with those in gray in friendly intercourse, and good-natured dialogues were indulged in.”

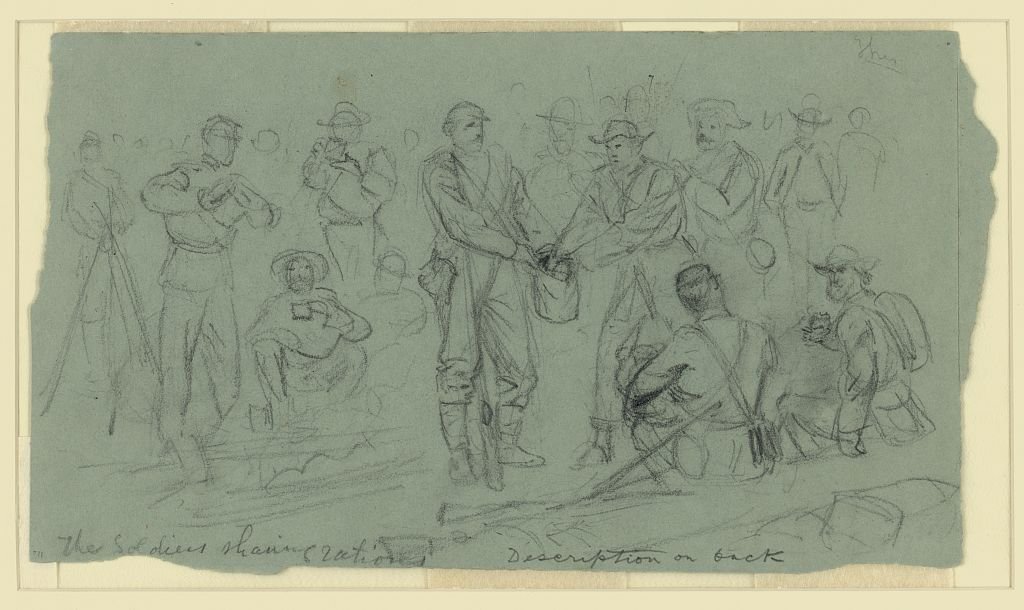

The war now over, the hungry Union soldiers shared their limited rations with the starving Confederate troops. Soldiers shared tales of their travels and fights. Once bitter enemies now embraced the relief that the suffering and strife was over. Corporal Smith from 1st Division related the scene:

“The sweet aroma of real coffee staggered the Confederates, condensed milk and sugar appalled them, and they stood aghast at just a little butter which one soldier, more provident than his fellows, happened to have preserved. A Johnny looked at the bit of butter a moment, as if trying to remember where and when he had been acquainted with its like before, and then asked in astonishment : “ Do they give you rations like that ? “ Gracious for such, to them, bountiful entertainment, the visitors lingered about for hours, comparing incidents of fight and march and bivouac and exchanging trinkets and scrips to be retained as mementos of the occasion.”

The War’s End: Relief, Tragedy, and Celebration

The next few days gave V Corps a chance to rest their weary legs. But they also had to oversee the collection and destruction of the Confederate weapons. Rebel regiments were supposed to line up and drop their weapons at collection points around McLean House. They would then be given parole notices, acknowledging the end of their military service. The Rebels these parole notices to distinguish themselves from deserters or those who were still active combatants. But many units had simply dropped their weapons at the end of fighting and left for home as soon as the surrender was declared.

The surrender agreement called for a formal ceremony for the Rebels to give up their arms. Units from the V Corps were called upon to perform this duty. Corporal Smith described the scene of the surrender of arms on April 12th:

“Our bugle sounded and our solemn and eager lines were brought to the manual of the “ shoulder “— now called the “ carry “ — as a mark of respect. Acknowledging the courtesy by similar movement, the (Rebel) column wheeled to front us. Then each regiment stacked arms, unslung cartridge boxes and hung them on the stacks, and finally laid down their colors. And then, disarmed and colorless, they again broke into column and marched off again and disappeared forever as soldiers of the discomfited Confederacy.”

Generals Grant and Lee departed soon after the agreement was made, with Lee heading back to his family in Richmond while Grant returned to Washington. Other army corps from the Army of Potomac also returned. The war was over for the V Corps, but they remained at Appomattox. The quick march had left their supply wagons far behind them, so many units were without tents or other supplies. They even went without food for 2 days, as army logistics had not accounted for the Union soldiers giving up half of their rations to the starving Rebels.

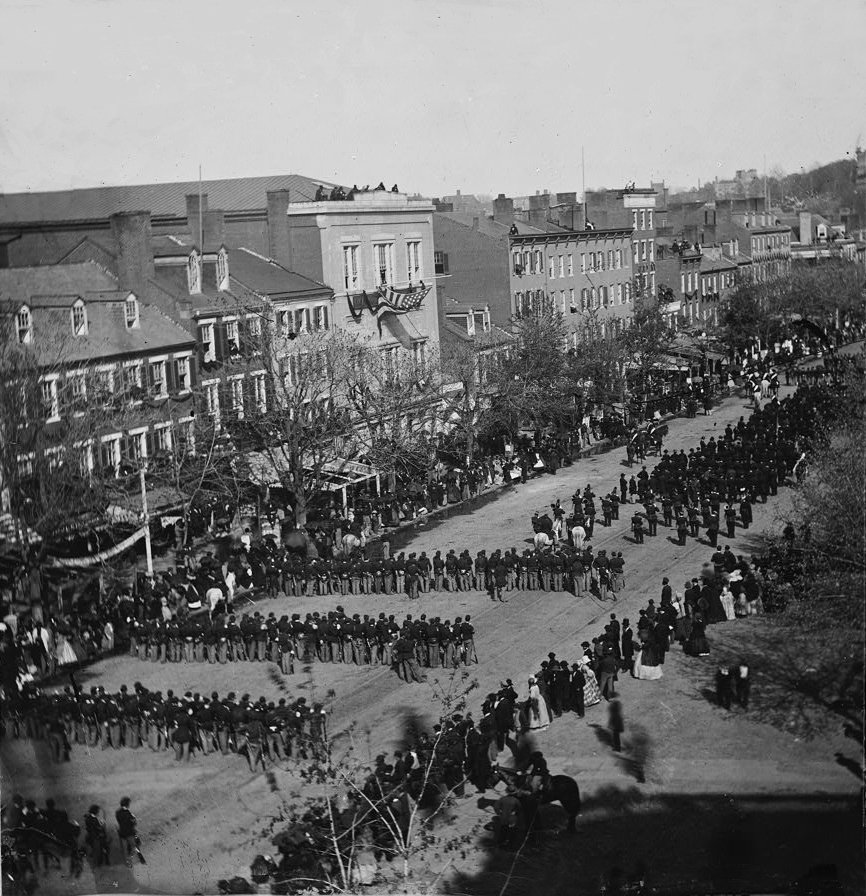

At noon on April 15th, V Corps began the long march back to Washington, D.C. with the promise of receiving food rations that night. Sadly, that was not to be the case, and they spent a cold, wet night still hungry. They reached Farmville, VA the next afternoon only to be hit with the distressing news that President Abraham Lincoln was dead.

Four days later, while still on the march, V Corps received orders to join the nation in mourning Lincoln as his funeral procession passed through the streets of Washington, D.C. It would be the first of many processions honoring Lincoln as his body was taken by train back to his home in Illinois. Lieutenant Woodward described the scene:

“On the 19th, as they were about moving, orders came for them to remain in camp, it being the day of the interment of Mr. Lincoln. All work was suspended, and at the time fixed for the movement of the funeral cortege, the regiments were drawn up in their camps, the brigade bands performed solemn dirges, and minute guns were fired.”

V Corps finally arrived at a temporary base back at Sutherland Station on the next day, April 20th, where they could enjoy a decent meal and access to hospitals and other conveniences of camp life. They soon began patrols, performed sentry duties, and guarded the Southside Railroad line from their camp on the outskirts of Petersburg.

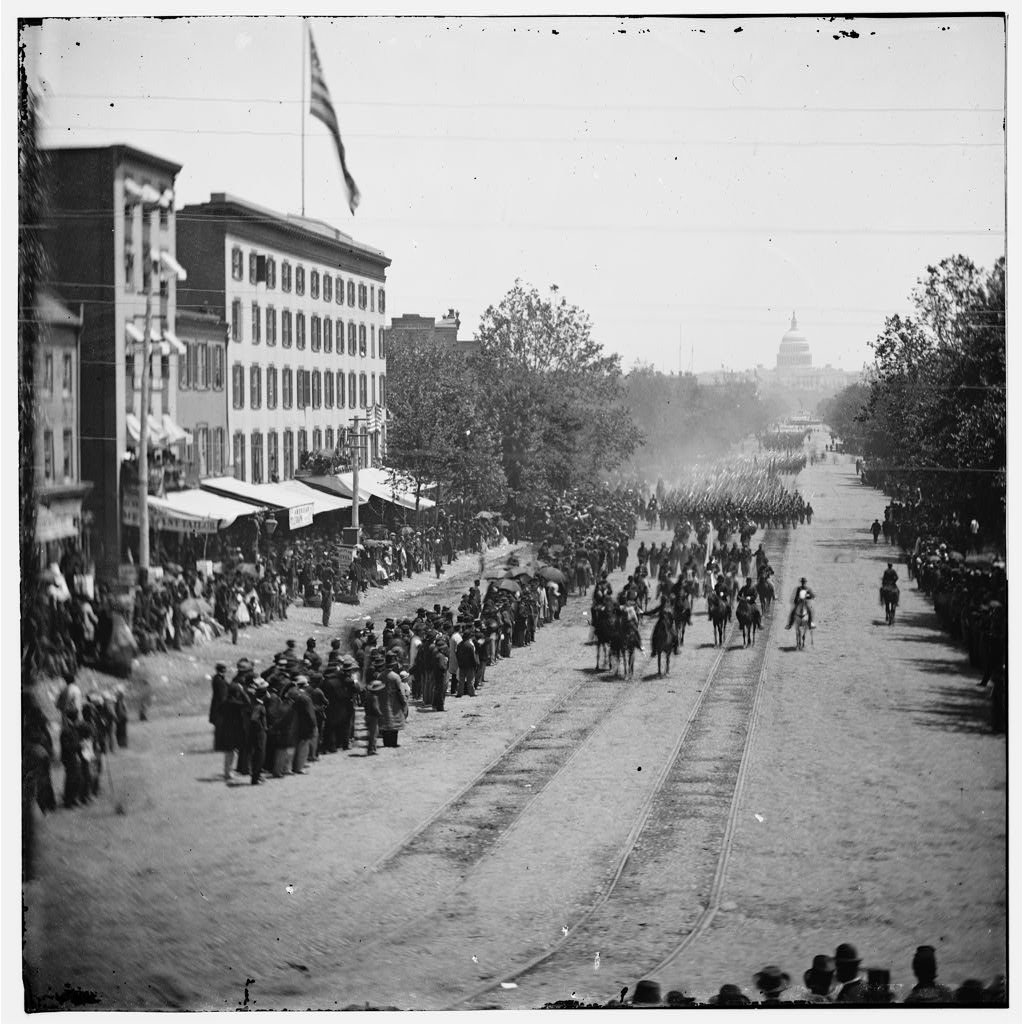

On May 2nd, V Corps began the long march to Washington, DC. They marched through the ruined city of Richmond, then crossed a pontoon bridge across the James River. On May 6th, III Corps and V Corps were reviewed by Generals Grant and Meade (commander of the Army of the Potomac) as they marched through the former Confederate capital of Richmond. They then marched on to Fredericksburg and finally arrived in Arlington, VA, just across Potomac from the capital, on May 12th.

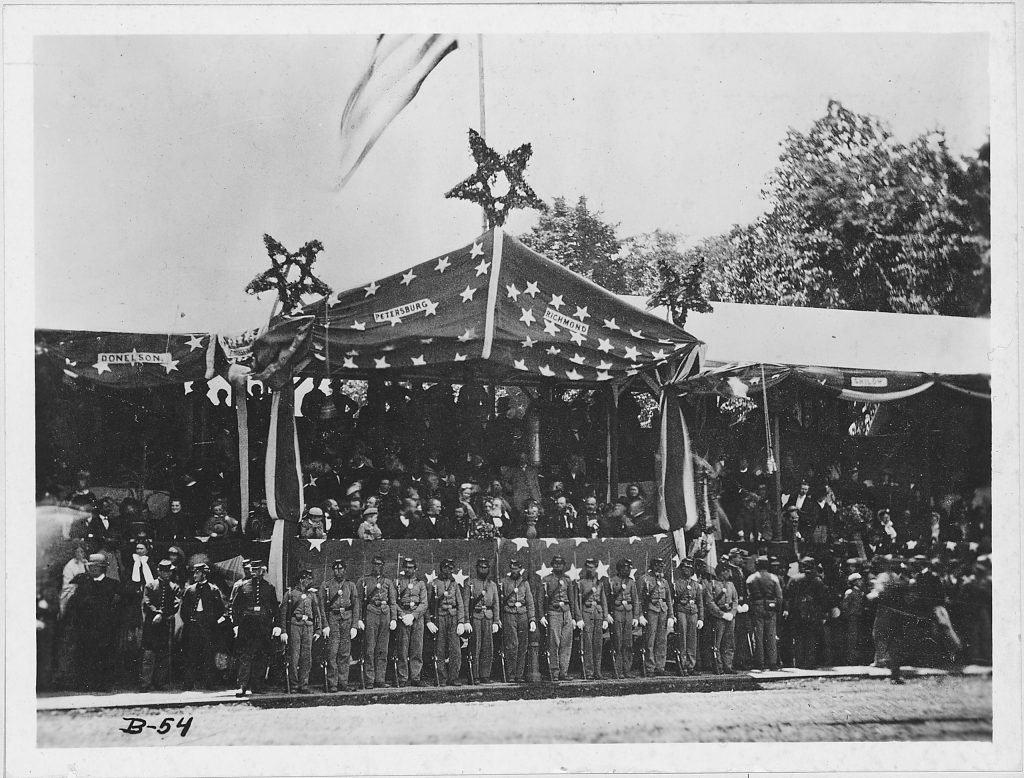

Then on May 23rd, the Army of the Potomac, with V Corps and other units of the Union Army, marched to Washington D.C. for a celebration called “The Grand Review” to honor the troops. The army corps marched down Pennsylvania in front of the new president, Andrew Johnson, their commanding generals, and a crowd of tens of thousands of residents. Corporal Smith, from 1st Division, described the scene:

“The grand old Army of the Potomac, which for four long years had bared its breast to rebel foes, crossed Long Bridge and received a royal welcome from those it had safely defended. What a sight we saw! Everywhere our national emblem was displayed. The artillery sent forth its thundering notes. The stirring music of the bands; loud and long continued cheering of the people, who thronged every available space; even innocent childhood was there to greet us with flowers, and our guardian angels, loyal and true womanhood, received us with their kindly smiles and words of welcome. With steady tread we marched over the broad avenue, receiving one continued ovation. Recrossed the Potomac River, and arrived at camp early in the evening.”

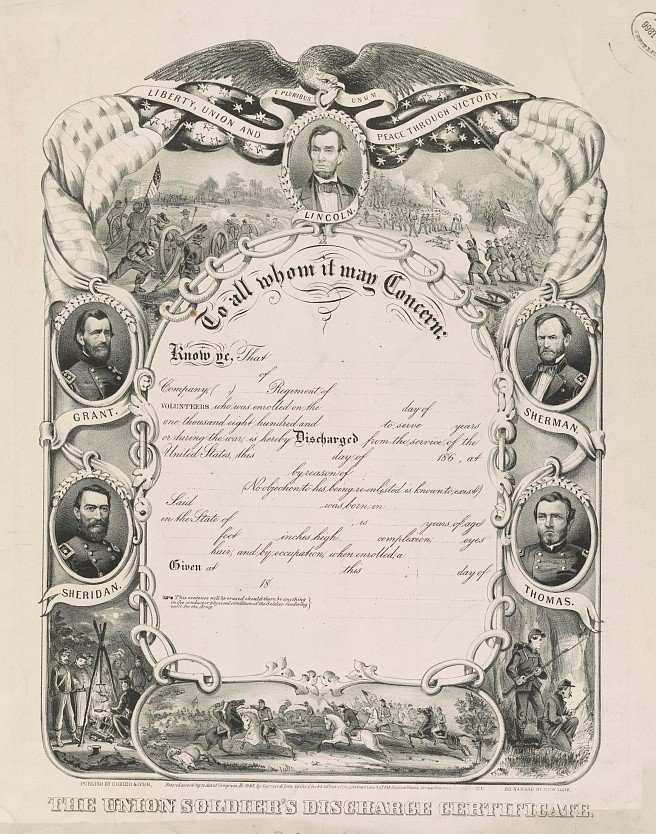

With the war over, the federal army disbanded most of the regiments of volunteers and state militias. The new Union army would be streamlined with full-time soldiers. Many of the younger officers and professional soldiers stayed on with the army. But for volunteers like my great-grandfather Nelson Hughes, it was time to go home.

Nelson’s 94th New York Infantry Regiment was one of the last of the volunteer regiments to be mustered out of the Army of the Potomac. But from the end of May 1865 onwards, soldiers in the 94th NY Infantry and other regiments in V Corps were mustered out of the army a handful at a time. It was likely just a matter of how long it took for the paperwork and payouts to be done.

My great-grandfather was mustered out from his camp in Arlington, Virginia on June 24, 1865, with 4 others from his regiment, a full 5 months from when he enlisted on January 25, 1865. He was one of the lucky ones. Of the 170 soldiers who entered the 94th Infantry from January 10 - 31,1865, most came out relatively unscathed. Sixty-three men were mustered out or discharged in June or July 1865, but there were also 13 who were wounded in battle. There were 12 disabled from combat (mostly from Company F), and 9 who were hospitalized for sickness. The only known deaths among this group were 3 killed in action and 4 that died due to sickness. For V Corps, the total of dead, wounded, and missing during their main period of action in 1865—the Appomattox Campaign — was 2,561.

Not only did Nelson emerge relatively unscathed, this 19-year-old Canadian farm boy had seen 2 American presidents — Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson — with his own eyes. On multiple occasions, he saw and fought under 3 of the most iconic Union generals of the war — Grant, Meade, and Sheridan. He traveled through 3 of North America’s great cities of the time—New York City, Washington D.C., and Richmond, VA. He also took part in the most consequential battle of the past year—the Battle of Five Forks. His 3rd Division not only played the most consequential role on that day, by getting behind Confederate lines and causing the Rebels to flee, they also helped to capture thousands of Rebels.

To top it off, Nelson’s 3rd Division and V Corps beat the wily General Robert E. Lee on the battlefield at White Oak Road. Then they played a big part in pursuing the retreating Rebels and blocked them at Appomattox, forcing Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia to surrender. It was quite an action packed 5 months.

After arriving back in upper New York and crossing back into Canada, Nelson would soon join a Canadian militia to fight the Irish immigrant rebels during the Fenian Raids — an uprising against the British authorities in Canada. Then he would move on to Minnesota and Canada, become a farmer, raise a family, and join his fellow veterans swapping war stories at the Stillwater, MN branch of the Civil War veterans’ association — the Grand Army of the Republic. It was a life well-lived.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.