Part 2: An Officer, a Gentleman, and a Divorcee

Before coming to North America in 1620, some of the Pilgrims tried living in a country much closer—Holland. Several families moved there in 1608, but found the society too liberal in accepting different beliefs and ideas. So they moved back to England for a time, before heading across the Atlantic in 1620.

The Pilgrims were mostly farmers or tradespeople of modest means. It was very expensive to finance the cost of supplies, sailors, and a ship to cross the ocean and back. So the group made contracts with the Plymouth Company that had the land rights to settle a section of New England. The investors in the company provided funds for the start-up and then the colonists would trade with the Native Americans or raise their own crops to repay their debts. Virginia had become profitable from growing tobacco.

In the era of exploration and overseas settlement, trading companies sprung up, backed by royals or pools of investors who would provide funds to get a settlement started. These debts would be repaid in gold or other valuable commodities, like animal furs, tobacco, or lumber.

The problem was that as the years went by, Plymouth was not a very profitable colony. Plymouth was too cold to grow tobacco and the land they chose near the water was too sandy. The animal skin trade also had competition from other areas. Plymouth could not repay their debts, so some creditors walked away. Others made new contracts with the settlers, restructuring the debt and making settlers personally liable for the debts.

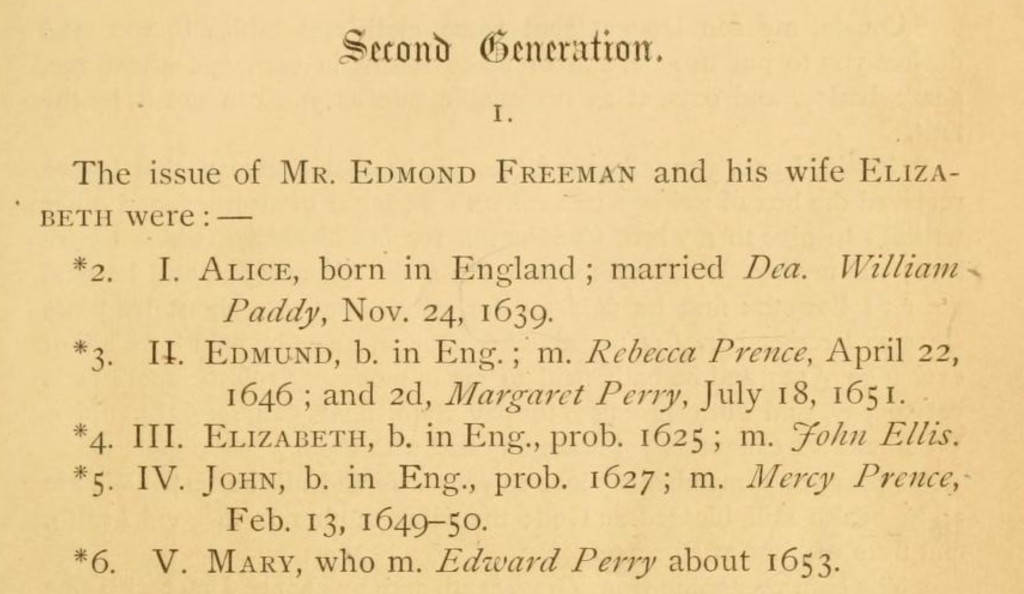

The Gentleman - Edmund Freeman

One of those creditors was John Beauchamp, a London clothing merchant who invested in the colony through the Plymouth Company and continually tried to get payment on the debt. Luckily for Beauchamp, he had a brother-in-law who wanted to move to New England and could look after the Plymouth investment. Beauchamp’s brother-in-law was none other than my 9x great-grandfather, Edmund Freeman.

Edmund Freeman arrived in Boston with his family in 1635 on the Abigail with other friends and relatives. Though not noble, Edmund had a title of “Gentleman,” which was listed on the passenger list. The “gentleman” designation was traditionally the lowest rank of the landed class in England. Traditionally, it also denoted that he came from a good family. In many Plymouth Colony and town records, his name was usually preceded by “Mr.” which was reserved for only a few individuals in his era.

Edmund had a plan to start a new settlement. He, his wife Elizabeth, and 4 children initially stayed in Saugus (aka Lynn, MA), where the other “10 Men of Saugus” who founded Sandwich town were. The History of Lynn notes a gift that Edmund presented the town there:

“ This year many new inhabitants appear in Lynn, and among them worthy of note Mr. Edmund Freeman, who presented to the Colony twenty corsletts, or pieces of plate armor.”

Edmund had better connections in Plymouth, so in searching for land for a settlement, he made efforts to move to Plymouth colony and was admitted there as a freeman in January 1637.

We don’t know the full details of how Edmund arranged his group’s move to Sandwich, but based on his brother-in-laws ties and his later service as Assistant Governor, we can assume his connections played a role. The Governor of Plymouth Colony at the time was William Bradford, who, along with other original Plymouth settlers, was personally liable for the debts to the Plymouth Company investors. By helping Freeman, Bradford would have an ally in his dealings with Beauchamp and the other London investors. Also, Edmund Freeman, with his position as a gentleman, was presumed to be an exemplary member of society and could offer leadership and connections to the colony.

However everything came together, 18 months after he arrived in Massachusetts, Edmund had recruited his group of 9 other proprietors and secured the rights to settle and take a share of land in Sandwich (with Edmund having the largest share). As noted in my last post and above, these original settlers are known as the “10 Men of Saugus.” Five of them, including Edmund, were men of means, while the others were skilled in trades (like my 8x great-grandfather Thomas Tupper, a shoemaker).

The Plymouth court made the settlement legal on April 3, 1637 and the group divided up the initial plots of land, likely by choosing lots. There were some who received more land due to either their financial contribution to the effort or the labor they put into the project (including working for the town government).

With land divided up amongst the initial 10 proprietors, other land was offered to friends and acquaintances from Saugus and other towns. The initial allowance was for up to 60 families to settle there and this was the total of families there in 1650, according to town records.

After settling in, Edmund took up a variety of colony and town roles. He was the head of 3 judges to the local court that served several towns in Cape Cod. He was also elected Assistant Governor from 1640 to 1646, assisting both Bradford and Edward Winslow, who alternated as Governor of the colony for many years. Elections were held every March with votes by the registered “freemen” of the colony (meaning not women, servants, or visitors).

The 1640s were a difficult time to find experienced leaders in Plymouth, as the original settlers were aging and dying off, so Edmund’s contribution was likely appreciated. During this time, there were also discussions on the repayment of the original Plymouth settlers debts, which the London investors claimed was 1,200 pounds. Edmund was one of 3 local agents for the investors, serving as an intermediary. Finally, in 1646, the 5 remaining debtors (which included Governor Bradford) transferred lands in Plymouth to Edmund Freeman as repayment for the debts. Presumably, Edmund then transferred money or his own lands in England to the London investors.

With the business of the Plymouth debts settled, Edmund eased out of public service. Perhaps there were hard feelings from Bradford or Edmund grew tired of mediating the various conflicts that arose in state and religious matters. Another issue that occurred in 1646 was the failure of an initiative that Edmund favored. This initiative would have allowed for more toleration of differences in religious practice, which Sandwich and other Cape Cod residents favored. From this point onwards, citizens were fined for failing to attend church, socializing with Quakers, and other trivial matters.

We can see Edmund's resistance against the Plymouth church regulations on several occasions. Edmund and Elizabeth were fined in the 1651 with 11 others for not attending church regularly (some Sandwich residents were not pleased with the pastor, and when he departed they went without a pastor for 20 years). Their daughter Mary also married a Quaker convert, Edward Perry, which must have been a great scandal in the eyes of the Plymouth court. The Quakers began meeting monthly in Sandwich in 1658 and the colonial government appointed a special marshal to investigate. In 1659, Edmund was fined 10 shillings for not cooperating with the marshal's investigation, which involved his son-in-law and other friends in the town.

By this time, Edmund had a considerable real estate empire in Sandwich to manage, having bought up land from some initial settlers who departed. He also had a growing family for whom he provided well for, even in spite of their social and legal indiscretions over the years.

The Officer - Lt. John Ellis

Edmund’s eldest daughter, Alice Freeman, married in 1639 after the family had settled in Sandwich. His second daughter, Elizabeth, took fancy with a sailor named John Ellis, who moved to Sandwich in the early 1640s (Ellis first appeared in public records in 1643 as being authorized to carry a gun). Unfortunately, John and Elizabeth were discovered to have had pre-marital sex (and a baby in 1644) before they were married in 1645.

In those days of the Puritan colonies, adultery and other sex-related indiscretions made up roughly one-third of the court cases in Plymouth, with 11% being for pre-marital sex. Punishments varied from fines to public flogging, the severity of punishment depending on whether the couple had already decided to marry or not. We don’t know if Edmund was one of the court judges to decide the punishment. But, whoever made the decision, my 7x great-grandfather John was flogged in public with his future bride made to watch. Today, you can find the Ellis case examined in dozens of blog posts and academic papers on gender studies and social studies of the Puritan age.

John and Elizabeth evidently got over the shame of a public flogging and raised a big family that did very well during the colonial years. John’s main public activity was helping with road construction and other public works projects in the colony. He was also part of the militia for over 20 years, serving as a lieutenant. Sadly, his life seems to have been cut short in 1677 during the largest uprising of the Native Americans during the colonial era, known as King Philip’s War.

John and Elizabeth's son Matthias, my 7x great-grandfather, was also active in the militia but managed to survive all the different conflicts that mainly occurred in other parts of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies. Matthias also cared for his grandparents, Edmund and Elizabeth, in their elder years on his farm in Sandwich (Edmund lived till he was 92). The Ellis name continued in my family tree for a total of 4 generations in America, until Matthias' grand-daughter, Jane Ellis, married into the Tupper line, when she married Prince Tupper in the mid 1700s (the Tuppers were introduced in Part 1).

Some of the well-known descendants of Edmund Freeman include Bing Crosby, Bette Davis, Marilyn Monroe (again), Commodore Matthew Perry, Orville and Wilbur Wright, Johnny Carson, Norman Rockwell, James Taylor, Lisa Marie Presley, Jodie Foster, and Bill Nye the Science Guy.

The Divorcee - Thomas Burgess Jr.

Another ancestor who arrived in Sandwich with the founders was Thomas Burgess Sr. Thomas was not one of the original 10 proprietors, but he and his wife Dorothy moved to Sandwich in 1637 with the other original settlers and his descendants remained there for many generations. He apparently had come to Massachusetts in the initial Puritan migration of 1630 and first settled in Salem.

Thomas Sr. was active in a number of local town and colony roles, such as road surveyor and deputy to the court in Plymouth. He built up a large land-holding in Sandwich over the years, as did his son John (my 7x great-grandfather), who had land in neighboring Yarmouth town. In the 1660s, Thomas’ farm was next to Edmund Freeman’s house in Sandwich (I believe on today's Tupper Road, near to the Saddle and Pillion Cemetery where Edmund and Elizabeth are buried). The proximity of the two families probably helped bring their grandchildren Matthias Ellis (John and Elizabeth Ellis’ son) and Mary Burgess (John’s daughter) together in marriage.

Another son, Thomas Burgess Jr., was the source of some grief for his family. Thomas Jr. in May 1661 was charged in Plymouth court “to answare for a fact of uncleaness comitted by him.” Before the judgment Thomas Sr. had to put up a 100 pound bond, while his father and brother-in-law each had to put up 50 pounds. After 13 years of marriage to Elizabeth Bassett, Thomas Jr. committed adultery with the 25-year-old Lydia Gaunt. Elizabeth applied for and received a divorce, receiving one-third of Thomas Jr.’s estate. She also received a variety of goods, according to the court records:

“att the same time the Court did allow her an old cotten bed and bolster, a pillow, a sheet, and two blanketts, that were with the paire of sheets, with some other smale thinge”

Elizabeth remarried some years later and Thomas and Lydia also married and moved off to Rhode Island. As marriage in the Puritan society was a civil matter, there was not any idea of sin attached to the divorce as in some Christian denominations. Though adultery, of course, was deemed a sin to be punished. The practice of divorce seems to have been rare in the colony. Thomas and Elizabeth’s divorce was the first one ever recorded in the 41 years of Plymouth Colony.

Some children of my 8x great-grandfathers Edmund Freeman, Thomas Burgess, and Thomas Tupper remained in Sandwich for several generations. However, others moved to towns further up Cape Cod or further west in Massachusetts or Rhode Island. I also have several ancestors who were early settlers of Rehoboth, MA, a town that was founded in 1643 near the border of Rhode Island.

At the moment, not much is known about the other personalities and family lines of my other Cape Cod area ancestors from my father’s side of the family. However, on my mother’s side there are at least two great-grandfathers who moved to the Sandwich area in 1639. We shall explore their stories in the next post.

Thanks for reading! Until next time.

Plymouth Colony Book List

Plymouth Colony: It's History & People 1620 - 1691

This book by Eugene Aubrey Stratton is a great introduction to the history and genealogy of Plymouth Colony. As someone with dozens of ancestors who settled and lived in Plymouth Colony, this book was essential to learning about them. Along with great genealogical details, you will learn about the social, religious, and political history of Plymouth Colony and the various towns the sprouted up there.

Sandwich: A Cape Cod Town

This book, published by Sandwich Town, presents the complete history of Sandwich with details from the town's archives. This book was an essential resource for me in learning about my Sandwich ancestors. Two of my 8th great-grandfathers -- Thomas Tupper and Edmund Freeman -- were 2 of the original proprietors, aka "The 10 Men of Saugus."