Much to be Thankful For

Thanksgiving is a time to celebrate a year of hard work and to give thanks for the blessings you’ve had during the year. Sometimes it is also a time to be thankful for surviving a dreadful year, with a hope of better days and years to come. This latter mode was how the first American Thanksgiving was for the Pilgrims in 1621.

Most know the story of how the Pilgrims left Plymouth, England, in 1620, hoping to find a place in North America to enjoy religious freedom. However, many perhaps know little about who they were or where they were really from. Many are likely unaware that the leaders of the Pilgrim group actually began their search for freedom in Holland before coming to America.

The Netherlands, a Refuge for English Separatists

Future governors of Plymouth Colony, John Carver, William Bradford, and Edward Winslow, all had moved to the Netherlands between 1608 and 1617. Several provinces in the Netherlands had revolted from Spanish (Catholic) control in the 1500s. In 1579, an agreement, called the Union of Utrecht, united various kingdoms and provinces in the Netherlands. The document also laid out that, “each individual enjoys freedom of religion and no one is persecuted or questioned about his religion.”

In England at that time, everyone was a member of the Church of England, headed by the monarch, and legally required to attend church. So the Dutch declaration of freedom of religious practice and freedom from persecution attracted many English protestants who wished to attend churches, read from prayer books, and listen to pastors of their own choosing. It also attracted people who were fleeing from France and other Catholic countries that were subjecting protestants to arrest and execution (such as the Huguenots).

One group of Pilgrims who moved to Holland had been meeting in Scrooby, England, at the home of William Brewster, a former diplomatic aide in London who had traveled to Holland previously. Pastors such as Richard Clyfton and John Robinson would give sermons at Brewster’s home and at others in the area.

Eventually, the local bishop investigated these groups, and Brewster and others were called to court for questioning about their activities and their absence from regular Church of England services. Brewster failed to appear in court twice and was fined 20 pounds (the equivalent of 6,700 pounds today). By separating from the Church of England congregations and religious practices, Brewster and other separatists were breaking the laws set by the head of the church, the king of England.

The Leiden Congregation

To avoid imprisonment and persecution, in 1608, Brewster and Rev. Robinson led Bradford, Carver, and others to Amsterdam to join fellow Church of England separatists. Others from their congregation followed in the succeeding years. After a year there, they moved to the bustling town of Leiden, where many English settlers had found work in the growing textile industry.

While people of all religions were free to practice their religion at home in the Netherlands, there were limitations to public worship. The local magistrates controlled who could open churches, so Robinson’s congregation and others like it met in private homes.

Life in Leiden was hard and many of the English suffered economically, many being landless and having limited incomes. Life as a tailor, leather worker, or textile worker was not a high-paying job. The settlers also worried about the prospects of their children’s careers and religious salvation. They wondered if their children would even continue to be English speakers in the future.

The Promise of Virginia

As news spread of the success of John Smith’s Virginia Colony, the English leaders in the English Leiden church explored the idea of moving to North America. They wrote to Captain John Smith about settling there. They also dispatched leaders to London to negotiate with the Virginia Company. A Dutch company also proposed to the Dutch Prince of Orange to send a group of 400 English Christians, led by Rev. Robinson, to settle in the Hudson River valley (a different group would settle there in 1624, it would become New Amsterdam, now known as New York).

The initial attempt to negotiate directly with the Virginia Company failed, perhaps because of intervention by King James. Fortunately, a British merchant named Thomas Weston took an interest in financing a new colony. Weston arrived in Leiden and offered to form an investment group (which would be called the Adventurers).

In early 1620, John Pierce, from Weston’s Adventurer’s group, secured a patent for a land grant for the group in the area of today’s Delaware, just north of the Virginia Colony patent. With the terms of the agreement set, the group prepared itself to depart. The Leiden group would consist of mostly younger members in their 20s and 30s, like William Bradford (30) and Edward Winslow (25). Rev. John Robinson would stay behind with the larger congregation while the church’s Elder William Brewster (54) and Deacon John Carver (36) would provide religious leadership for the group.

In July the congregation gathered to send the lead group of settlers off to the new world. Around July 22, 1620, the group’s recently purchased ship, The Speedwell, departed the Dutch port Delfshaven. But trouble was soon to befall the expedition.

Back in London, John Weston’s investors had demanded a change to the 7-year partnership agreement they had made with the Pilgrims. Originally, the settlers (aka Planters) were to be granted ownership of the homes they would build. They would also be allowed to have 2 days a week to work on their own affairs (with the other 5 days spent planting, hunting animals for fur pelts, and working on behalf of the company). Now the investors wanted to keep ownership of the homes and require 7 days’ work for the company.

The Mayflower

In addition, the Adventurers had formed a separate group of settlers who were not members of the Leiden or Scrooby congregations (who were known as “strangers” in Pilgrim parlance). This group sailed on the Mayflower from London with supplies for the journey and settlement. They brought beef, hard biscuits, peas, barley, fish, butter, cheese, oatmeal, and beer (for its nutrition!) all financed by the Adventurers. They also brought tools, armor, weapons, and seeds for crops.

The Mayflower sailed from London to Southampton, where it met the Speedwell group. When the Pilgrims from Leiden learned of the new terms of the agreement, they refused to accept them. Since significant money had been spent already by both parties, the expedition continued on, only with poorer relations amongst the group and fewer supplies than expected.

In early August, the two ships departed Southampton for the new world. But the Speedwell began taking on water and the two ships put into Dartmouth port for repairs a few days later. On August 12th, the group departed again, this time making it a few hundred miles out to sea before the leaking on the Speedwell worsened. Again they turned back for England.

Back at Plymouth in southwestern England, the captain of the Speedwell declared the ship unseaworthy. They shifted supplies and passengers from the Speedwell onto the larger Mayflower, but not all could fit. After a month of discord at sea, two group leaders and several families with young children left the group to remain in England.

On September 6th, the Mayflower finally departed Plymouth for its “Virginia” (Delaware coast) destination. On board were 37 members of the Leiden separatist congregation. There were also 65 others from the Adventurer’s organized group who were mostly regular Church of England members (many of whom had a low opinion of the separatists).

The Atlantic Crossing

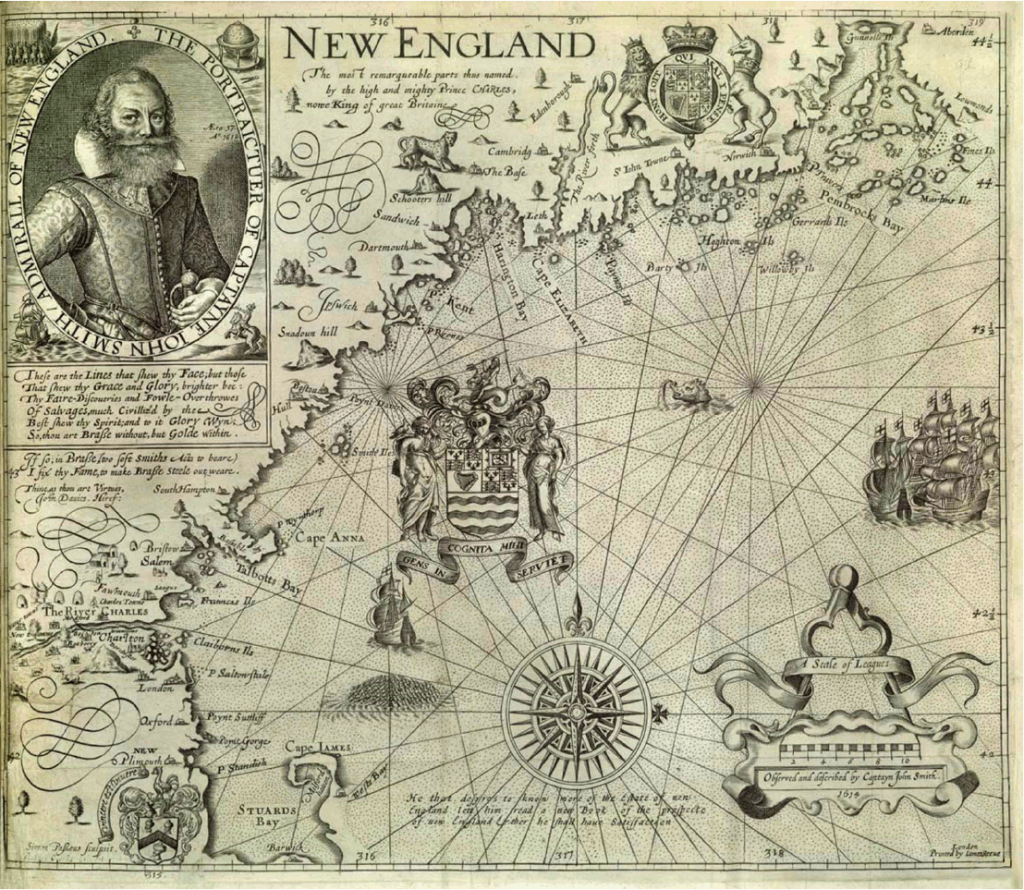

The late crossing was rough, and storms blew them off course. A main beam on the Mayflower was nearly shattered in the seas. The Pilgrims had the letters and books from Virginia’s Captain John Smith with them, as well as his maps of the New England and Virginia coast. But rather than arriving just to the north of the original Virginia colony, between Virginia and today’s New York, the first land they hit was Cape Cod.

According to William Bradford, the seas were too rough to go around Cape Cod, so the Mayflower sailed back to the shelter of the Plymouth bay side of the cape. Some have speculated that the Pilgrims intentionally settled beyond the land grant of Virginia to avoid the Church of England jurisdiction there. But we will never know. Bradford blamed their rogue landing in Plymouth Bay on their ship’s captain, Christopher Jones. Among the ship’s 30 crew members, only one had previously crossed the Atlantic. (John Pierce would secure a new royal patent in 1621 for the land in New England where the Pilgrims landed).

They set anchor on November 11, 1620, off the shore of today’s Provincetown Harbor. One crew member and one servant of a passenger had died during the crossing, and a baby had been born. The baby was named Oceanus.

The Mayflower Compact

Given the fact they had landed well north of the Virginia colony, the settlers had no backing under English law to the land before them. The disagreement over the terms of their partnership with the Adventurers had continued during their journey across the Atlantic. Some in the non-separatist group advocated for striking out on their own.

Fortunately for the Pilgrims, cooler heads would prevail as they realized the challenges that faced them arriving with winter already upon them. They came to an agreement and created a document to state the terms of the colony’s operation. The Leiden church Deacon, John Carver, had been one of the Leiden church’s negotiators in London, and now he negotiated and wrote out the compact that would govern their association.

In this Mayflower Compact, on November 22nd, the 41 men in the group signed their agreement to remain,

“the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James… (and) Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience.”

Once the compact was signed, the 41 men, servant and master alike, voted on a leader. Again, they chose John Carver.

Exploring the Cape Cod Coastline

While matters of colony governance were discussed, the Mayflower crew had been fixing the ship’s small sailboat that had been damaged in the storm. A party of a dozen men eventually went ashore to explore their surroundings.

At one point, they spotted a group of natives and pursued them for 10 miles. They also discovered a supply of dried corn that appeared abandoned to them (they would compensate the natives later for the corn and other items they took). In another place, they found native homes made from logs and animal skins. The colonists found the insulation in the homes superior to that found in some English homes.

On December 6th, a group took their sailboat to explore the bay for a place to build their settlement. The area where they first landed did not offer sufficient water or land for farming, After several days, one of which they were attacked by natives, they found a place with a good stream, harbor, and a clearing of land. On examining John Smith’s maps they determined it was the place Smith had named "Plimouth," and chose this as its name.

Upon returning to the Mayflower, they encountered bad news. William Bradford’s wife Dorothy had fallen overboard and drowned the day after the explorer group had departed. More deaths would soon follow.

The Mayflower lifted anchor on December 15th and headed through the wind and sleet to their chosen spot at Plymouth. The place they had chose was near an abandoned Wampanoag village of the Patuxet. This was the band of natives that Squanto was from. Little did the Pilgrims know, but several groups of traders and explorers had passed along the New England coast kidnapping natives. With them they brought disease that had wiped out Squanto’s group of Patuxet and decimated other groups.

Building a Colony and Community at Plymouth

Disease and malnutrition was to hit the Pilgrims hard as well. Four others died in December along with Dorothy Bradford. Most of the group stayed on the Mayflower while those well enough cared for them, scavenged for food, and began building shelters on land. Eight more died in January, including Rose Standish, wife of former English soldier and future Plymouth militia leader Myles Standish. Seventeen more died in February and thirteen more in March, including Edward Winslow’s wife Elizabeth. In some cases, whole families would perish.

It is likely that the entire group would have died without external help. This came, unexpectedly, in the middle of March. A lone native man walked into the Pilgrim’s settlement and headed directly to their common house. The Pilgrims were shocked at his appearance and even more surprised when he greeted them in English.

This was Samoset, who was from a tribe in Maine. It’s unclear what he was doing amongst the Wampanoag, but the English he learned from English fishermen made him a perfect liaison. Samoset explained about the kidnappings done by Thomas Hunt (which explained why they had been attacked further south). He also told them about a great plague that had killed the entire native population around Plymouth.

Samoset stayed the night and the next day the Pilgrims sent him off with several gifts and a message for the native leaders that they wish to trade. He returned the next day with beaver skins. Later in March, the settlers met Squanto and then the sachem (tribal leader) of the area, Massasoit.

Governor John Carver and Massasoit soon came to an agreement on trade and support between them. Most importantly for the Pilgrims, Massasoit agreed to a mutual assistance treaty with the Pilgrims, in case of attack on either of them. The plague that hit the area had decimated the Wampanoag villages under Massasoit’s domain. This left them vulnerable to the Narragansett and Pequot tribes further to the west that had suffered very little from disease. As Massasoit’s village was 40 miles away, he likely felt little threat from a small group in this deserted part of his realm.

The Pilgrim’s elected Governor John Carver and his wife would die in April, but the pace of deaths had trickled off. Squanto was to prove the savior to the survivors in the coming year. He showed them the best fishing spots and taught them how to plant corn and other crops native to that land. He also served as their translator and guide in dealing with various tribes.

The First Thanksgiving

In the summer, the Pilgrims discovered how bountiful the surrounding land was. The wild berries staved off the scurvy and the plentiful seafood helped restore their strength and health. As the fall harvest finished their Governor William Bradford decided it was a good time for a celebration. Rather than a religious thanksgiving ceremony, America’s first “Thanksgiving” was a three-day affair that resembled more of a harvest festival.

Massasoit brought 90 men to feast with the remaining 55 Pilgrims who had survived the first year. The sachem brought with him 5 deer to go along with the variety of turkey, duck, eel, and other fish the Pilgrims had caught. It’s surprising that this grand celebration and the harmony between the two people’s went unmentioned in Bradford’s history of that era. The only written record of the party was from a letter sent to England by Edward Winslow. However, the significance of this cultural interchange lies in the fact that Plymouth Colony residents maintained a largely peaceful existence with Massasoit’s people until his death in 1660.

The Financial Misfortune of the Adventurers

Soon after the celebration more guests arrived in Plymouth. The ship Fortune arrived with 35 more settlers and some supplies. The passengers included some family members of the initial group and more hardy young men recruited by the Adventurers. With extra mouths to feed over the winter, Governor Bradford cut the daily rations in half to ensure enough food for all. Fortunately for the Pilgrims, the death rate would lessen significantly in the coming years (though it was the opposite for their native neighbors, whom were vulnerable to the spread of Eurasian diseases).

The Fortune would be the only ship of new settlers bound for Plymouth that the Pilgrims would see for the next two years. Unfortunately for the Adventurers investment group, on its return to England, the Fortune would be intercepted by French pirates and stripped of its cargo of wood and fur pelts. The Mayflower had also returned home empty in April 1621. In 1622, a third ship bound for Plymouth would be forced to return to England. With meager prospects of success, many investors would soon sell off their shares in the company at an enormous loss and the flow of supplies and settlers would stop for several years.

While Plymouth was a slow growing colony, its proximity to plentiful seafood and wild game would provide ample protein source for the settlers and later arriving immigrants. The land was also sufficient to grow fruit and vegetables in greater abundance than they were used to in England. The population of English settlers in Massachusetts would not swell until 1630 with the arrival of 11 ships to Boston harbor, now known as the Puritan Migration to New England.

The Pilgrim Descendants

The surviving Pilgrims would do well and live mostly in harmony over the succeeding years. Each year, they would elect their leaders, a governor, and several assistants to serve as magistrates and members of the colony’s council. A great-grandfather on my father’s side, Edmund Freeman, would serve as an assistant governor to William Bradford in the 1640s. Another great-grandfather on my mother’s side, Samuel Hinckley, would see his son, Thomas, become the last governor of Plymouth Colony, before the British combined Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies into one province in 1691. (The governor who preceded Thomas Hinckley was Josiah Winslow, Edward Winslow's son).

Famous great-grandchildren of long-serving governor William Bradford, include Noah Webster (creator of Webster’s Dictionary), Jane Austen, J.P. Morgan, Jane Fonda, Hugh Hefner, Alec Baldwin, Clint Eastwood, and Sally Field. Former governor Edward Winslow’s great-grandchildren include: President Calvin Coolidge, Orson Welles, Bing Crosby, Ernest Hemingway, Richard Gere, and James Taylor.

Some of the less famous descendants include Bradford’s great-granddaughter Jerusha Bradford, who would marry into one branch of my father’s family tree. Edward Winslow’s nephew would also marry my 8th great-aunt Mercy Worden, daughter of my 9th great-grandfather on my father’s side, Peter Worden II. Peter Warden’s wife Mary or his sister may also have been a Winslow as Mercy was said to be a cousin of her husband Kenelm Winslow Jr., but the record in unclear.

Religious Life in Plymouth Colony: A Preview

The Pilgrim’s spiritual leader, Rev. John Robinson, would die in Leiden in 1625. In his absence, William Brewster would soldier on as the colony’s religious leader. But many from Robinson’s Leiden congregation would eventually make the journey to Plymouth. This would include my 9th great-grandfather Henry Cobb Sr.’s first wife, Patience Hurst and her family (Henry’s an ancestor from my mother’s side). Henry and Patience and my 10th great-grandfather, Samuel Hinckley, would become neighbors and fellow church members of Rev. Robinson’s son Isaac. All three were founders of Barnstable town on Cape Cod (the town just next to Sandwich, MA where many of my father’s kin settled). The lives of these Barnstable and Yarmouth, MA kin will be explored in my next blog post.

Happy Thanksgiving!

Great Books about the Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony*

*Note: The Blog will earn a small commission, at no additional cost to you, for any products purchased through affiliate links.