Nelson Hughes' First 2 Months in the Union Army

By the time my great grandfather Nelson arrived on the front line south of Petersburg, Virginia in 1865, over 600,000 people had died in the Civil War. Fifteen percent of all Union troops who entered the war would die, mostly from disease. One in thirteen men would lose an arm or a leg. What would be the fate for Nelson, his leaders, and the 170+ new soldiers that joined Nelson’s 94th New York Infantry Regiment in 1865?

While the Union was suffering more casualties than the South, the trends were even worse for the Confederate Army. The Rebels’ supply lines were being cut by General William Sherman in the south and General Ulysses S. Grant’s armies in Virginia. The Confederate’s overseas trade with Europe had been cut to 5-10% of pre-war levels thanks to a Union naval blockade. And the great population disparity between North and South spelled doom for any long-term success for the South. Nevertheless, the Rebels’ fighting spirit was strong.

General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia spent the winter months of 1864-65 building and extending 16 miles of trenches and other defenses around Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. General Lee’s supplies were so low that his army was subsisting mostly on cornbread. Yet many letters that Confederate soldiers sent home were still positive and hopeful.

General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac spent the early part of 1865 rebuilding their troop strength and planning what they hoped would be the last campaign of the war. General Grant’s strategy to attack Petersburg from the east and south in 1864 had put the Union in excellent position to extend the battle lines further west, weaken the Rebel’s defenses, and fully cut off Lee’s army from the south.

The Battle of Hatcher's Run

The first battle of the year in Virginia began during a break in the winter weather. Grant sent several thousand cavalry west on February 5th, 1865 to intercept the Rebels’ supply caravans on Boydton Plank Road. Grant also sent the V Corps, led by General Gouverneur K. Warren, to the south of Hatcher’s Run to shield the cavalry from any Rebel counter attacks. Nelson Hughes’ 94th New York Infantry Regiment was part of this shielding force, as part of the 3rd brigade of the 3rd division in V Corps. Two divisions of II Corps moved to fill in the gap between the V Corps and the Union Army’s other positions south of Petersburg, VA.

The Union was successful in extending the Confederate Army’s thin defensive line, but the Rebels were able to keep control of their supply route. The Union lost over 1,300 men to 1,000 for the Rebels. Meanwhile, the 94th NY Infantry had 33 wounded and 7 dead during the battle that extended the Union lines by 3 miles to the west towards the Rebel’s supply route along Boydton Plank Road. However, the Union Cavalry could only capture 18 supply wagons and 50 men in their attacks along the road.

I don't know if my great grandfather Nelson was with the 94th NY Infantry for this battle or not. It is possible Nelson was one of the 94th’s 221 soldiers fit enough for duty as they fought for control of the creek banks along Hatcher’s Run and Vaughan Road. It’s also possible that Nelson arrived a week or two after the battle, to replace the wounded and those whose 3-year contracts were up in February 1865.

The records of other new recruits in the 94th show illnesses and injuries that suggest Nelson might have been on or near the Hatcher’s Run battlefields. Two soldiers who enlisted the same week as Nelson were with the V Corps in Virginia by mid-February. One man was sick from February 16th onwards and another died on February 23 of smallpox in the 3rd Division’s Virginia field hospital. Two other men who enlisted that same week as Nelson were discharged for disabilities in March before any other battles. As the 94th NY’s next listing of casualties did not occur until March 29th, it seems plausible that these men and Nelson all fought at Hatcher’s Run. But it is also possible the two disabled men were injured during the daily volleys of cannonballs and gunfire along the front lines during February or March.

After the Battle of Hatcher’s Run ended, the 94th NY Infantry and the rest of the V Corps stayed and built up new defenses and quarters to consolidate the army’s gains. As the winter snow turned to spring rains, the muddy roads and swollen rivers made it impossible to move major forces.

Generals and Socialites Reviewing the Troops

The Virginia front was quiet for the 94th NY Infantry from the end of February through the end of March, with no major casualties during that time. Both Generals Lee and Grant spent the time planning their next moves.

From the letters of an aide to General Meade, Col. Theodore Lyman, we know the battlefront was quiet enough that the wives and daughters of Washington, D.C. society felt safe enough to travel from City Point, on the far right of the Union’s formations to the far left of V Corps. Some visitors included General Grant’s wife Julia Dent Grant, Defense Secretary Stanton’s daughter Eleanor Adams, and other socialites. Among the troops the group reviewed was Nelson Hughes’ 3rd division, lead by General Samuel W. Crawford. Lyman writes on March 8th,

“By the time the males had made a considerable vacuum in the barrel of ale, Griffin’s division was ready for review, and thither we all went and found the gallant Humphreys, whom I carefully introduced to the prettiest young lady there, and expect to be remembered in his will for that same favor! A review of Crawford’s division followed, very beautiful, with the setting sun on the bayonets; and so home to an evening lunch, so to speak, whereat I opened my “pickles,” to the great delectation of both sexes.“

The Confederate Army Attacks

From Col. Lyman, we also know that April 1st was the rough timeline for the Union’s attack. Grant finally gave orders on March 24th for movements and preparations for attacks on March 29th. General Lee, meanwhile, was debating whether to sue for peace, retreat, or attack. Lee’s final decision was to take the initiative and attack first. On March 25th Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia attacked the Union line at Fort Stedman, to the southeast of Petersburg. Lee’s plan was to take Fort Stedman and the Union’s rail line just 1 mile past the fort. Then the Rebels would travel 10 miles down the line to General Grant’s headquarters and primary supply base at City Point, VA.

The attack began at 4 a.m. with a few companies of men leading the way, carrying axes to chop down Union defenses. Fort Stedman was a mere quarter mile from the Confederate lines. The Rebels caught the defenders to the right side of the fort sleeping and overtook their positions. Then they moved to the rear of the fort and entered from behind, capturing the fort and two artillery batteries. Thousands more troops followed, as nearly half of Lee’s army had been mobilized for the attack.

Rebel forces did not make it much further than just beyond the fort. The lead Rebels hesitated in the morning darkness, unsure of what lay ahead of them. The Confederate cavalry also did not arrive in time for the battle. They had been telegraphed only 12 hours earlier and could not arrive from Richmond in time for the attack.

By 7:30 a.m. the Union forces from IX Corps on either side of the breech counterattacked and pushed the Rebels back. Union troops also attacked in other sectors along the line. By mid-morning, over 1,900 Rebel soldiers were captured and 1,000 more were killed or injured. In just a few hours, nearly 10% of General Lee’s army had been lost. The Union Army re-took control so quickly that hours later, America’s Commander-in-Chief felt secure enough to come down the same train line the Rebels had hoped to capture.

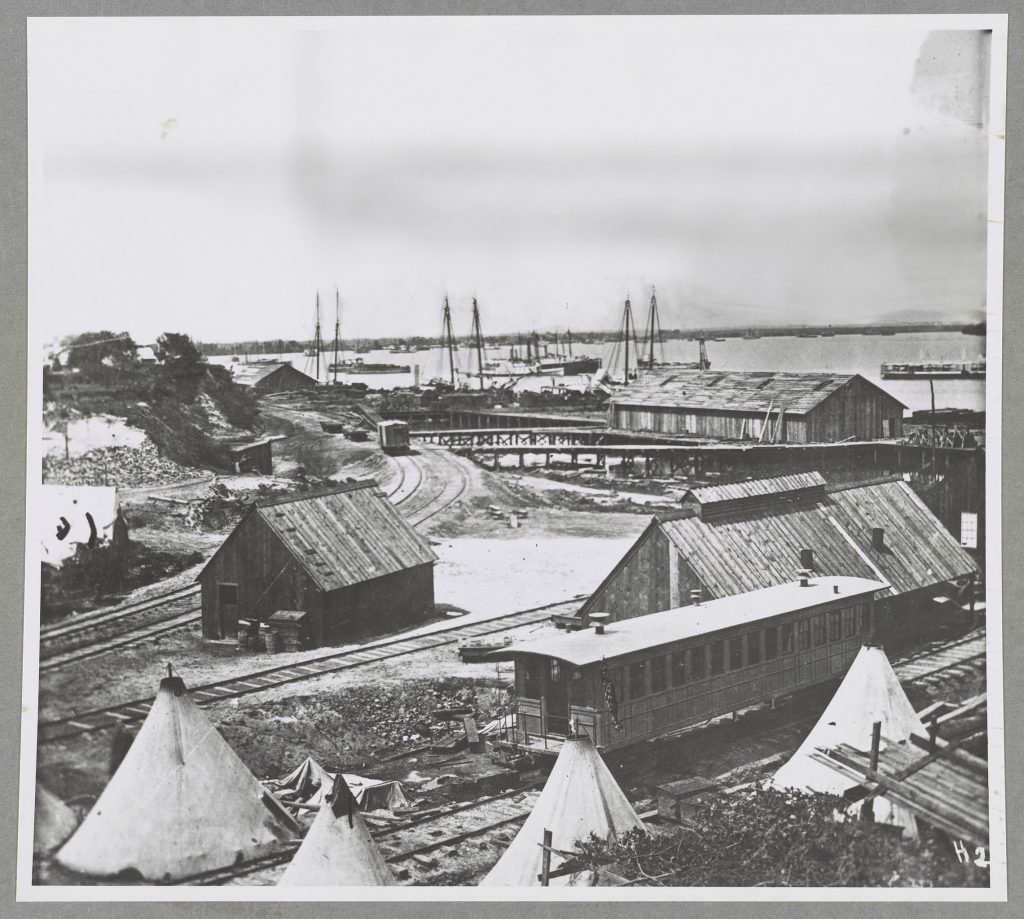

Lincoln at the Virginia Front

It’s unclear if Lee knew that President Lincoln and his family were at Grant’s headquarters in City Point, VA the very day of the Fort Stedman attack. The presidential entourage had arrived on March 23rd to confer with Grant, General Meade, and the other generals as they planned the coming spring campaign. Lincoln and his family would stay for 2 weeks, living on a steamship between meetings in Grant’s headquarters.

Lincoln also toured the battlefields and reviewed troops. In fact, after the Confederate attack on March 25th was repulsed, Lincoln took his train car past the lines behind Fort Stedman. Then he moved farther west to visit General Meade’s headquarters and also observed formations of V and VI Corps. General Meade’s aide, Col. Lyman, wrote about the occasion to his wife on March 25th:

“We may indeed call this a many-sided field-day: a breakfast with a pleasure party, an assault and a recapture of an entrenched line, a review by the President of a division of infantry, and sharp fighting at sundry points of a front of eighteen miles! If that is not a mixed affair, I would like to know what is?”

My Great Grandfather Definitively Encounters President Lincoln

The division that President Lincoln would review that day was none other than the 3rd Division of the Army of the Potomac’s V Corps. Yes, my great grandfather Nelson’s 3rd Division. According to an officer in the VI Corps, Lincoln’s review of troops that day was pre-planned. And Lincoln’s visit that day was significant enough for General Meade, Col. Lyman, and several soldiers to write their wives about it. General Meade had just come back from Grant’s City Point headquarters a few hours before Lincoln. He wrote to his wife the next day after she departed City Point:

Headquarters Army of the Potomac, March 26, 1865.

“Today is a fine day, without wind, and I trust you will have a pleasant journey up the Potomac and get safe home.

After I arrived here, the President and party came about 1 p. m. We reviewed Crawford’s Division, and then rode to the front line and saw the firing on Wright’s front, at the fort where you were, where a pretty sharp fight was going on.”

Col. Lyman fills in more details on the visit. Apparently, General Grant had also ridden up to Meade’s headquarters with Lincoln. Some accounts say Mrs. Lincoln was with them. From Lyman’s account, there doesn’t appear to be handshaking going on. In his March 26th letter to his wife, Lyman writes,

“... the President (who looks very fairly on a horse) reviewed the 3d division, 5th Corps, which had marched up there to support the line, and were turned into a review. As the Chief Magistrate rode down the ranks, plucking off his hat gracefully by the hinder part of the brim, the troops cheered quite loudly.

Scarcely was the review done when, by way of salute, all those guns you saw by Fort Fisher opened with shells on the enemy’s picket line,”

It must have been quite a day for Nelson and the 94th NY Infantry. First, their unit was called up to respond to the Confederate attack. Then they marched to the battlefield, and finally lined up for review by President Abraham Lincoln, who trotted by waving his hat as they cheered him on. Col. Lyman doesn’t mention handshakes with the troops, leaving my father’s story of a Lincoln handshake with my grandfather still uncertain.

However, we know from accounts on other days that Lincoln engaged in lots of handshaking with the troops, so it’s quite possible Lincoln shook a few hands that day. Elizabeth Keckley, Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress and confidante, relates a scene from April 7th, Lincoln’s last day in Virginia, before the family and entourage returned to Washington.

“The day before we started on our journey back to Washington, Mr. Lincoln was engaged in reviewing the troops in camp. He returned to the boat in the evening, with a tired, weary look.

“ Mother,” he said to his wife, “ I have shaken so many hands today that my arms ache to night.”

The 94th New York Infantry's Soldiers and Commanders

So many of the 94th NY Infantry (and likely many others in 3rd Division) were new that perhaps their new uniforms were part of the reason they were chosen for review by the higher ups. Union soldiers didn’t receive a replacement uniform until theirs was worn out. They had to pay for spare uniforms themselves. As noted earlier, over 170 new troops joined the 94th in the first 3 weeks of January, so their uniforms were still relatively new.

With only 220 plus troops being fit for battle in February and March, the unit was made up of many fresh faced and inexperienced soldiers. But their leadership had been with the regiment from before Gettysburg through the whole Petersburg Campaign. The First Sergeant of Nelson’s Company B was William Goldthrite from Champion, New York, 100 miles from Nelson’s hometown of Morrisburg, Canada. Goldthrite had enlisted as a private in 1862 at age 21. He was promoted to Sergeant in 1864, by which time he had been captured twice during battle.

Company B's Captain was Henry T Chester, the son of a Presbyterian minister in Buffalo, NY. Chester volunteered in 1862 as a private and rose through the ranks before being promoted Captain during the Petersburg Campaign in 1864. The commander of the entire 94th was 22-year-old Major Henry Fish from Buffalo, NY who had 2 1/2 years of experience in the army. And their Commander of Third Division, General Samuel Crawford, had been in the war since the beginning, having served as a Union Army surgeon at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina when the Confederates first attacked the Union in April 1861.

The men of the 94th New York Infantry Regiment and the others in the Army of the Potomac had been drilling for over a month. Four days after seeing President Lincoln, V Corps would march into their first of several battles. They would go on to become a big part of what is now known as the Appomattox Campaign, which stopped General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia before it could escape. In the next edition, we will take a detailed look at the action my great grandfather's unit took part in. Many from the 94th NY would pay the ultimate sacrifice, but the campaign would end in a Union victory and a dramatic meeting between Grant and Lee at the Appomattox Courthouse.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.