In January 1865, 19-year-old Nelson Hughes gave up his work on a farm in Williamsburg, Canada, crossed the St. Lawrence River, and joined the New York Volunteers. Little did he know that in the next 4 months he would cross paths with American icons, take part in decisive victories, and celebrate the war’s end with hundreds of thousands of people.

But first Nelson had to join the battle. His new unit, the 94th New York Infantry Regiment, had been fighting bloody battles in Virginia and Pennsylvania for nearly 3 years, and the 3 year enlistments for many soldiers were about to end. The 94th Regiment lost 250 men in 1864 because of dissertations, captures, battle injuries, sickness, and death. Some other New York units were in even worse shape. In January 1865, the 92nd New York Infantry had only 75 men and 7 officers left and had to be disbanded.

Rebuilding a Battered Army

To address the serious manpower needs, President Abraham Lincoln signed draft orders in July and December of 1864, calling for 500,000 new soldiers. Deadly battles at Antietam, Gettysburg, and around Petersburg between 1862 and 1864 had lowered enthusiasm for volunteers. Rich families who could afford it paid $300 to get their sons exempted from the 1863 draft. Those who didn’t have the cash mortgaged their farms. Thus, the burden for the war would fall on the backs of the landless poor. In response, poor Irish immigrants and other poor whites rioted in New York City in July 1863, attacking and killing state officials and the rich.

To avoid more riots in 1864, counties and towns offered larger bounties (bonuses) to attract volunteers to meet their quotas and avoid the need to draft those unwilling to go to war. Jefferson County, New York needed to recruit 1200 men for the July, 1864 draft call and hundreds more in December.

On January 5, 1865, the Jefferson County commissioners voted to offer $600 per volunteer for a commitment of 3 years of service (or $200 for 1 year, $400 for 2 years). Those joining for 3 years were given $100 up front and $13 per month for the ranks of privates and corporals, with the rest of the bounty payable after their discharge. By comparison, the average US farm salary, with board, was $13.66 per month in 1860 and a laborer working on the Erie Canal in 1865 could make $1.50 a day. Thanks to the bounties and upfront money, dozens of men in Jefferson County, like Nelson, joined up with the 94th NY Regiment in late January and early February 1865. However, it is unclear how quickly they were sent to the front lines.

Could Nelson Have Met Lincoln?

Nelson mustered into the 94th Infantry's Company B on January 25, 1865 at Watertown, NY. But it’s unclear when he was sent off to the front line. Watertown had a train line to New York City from where troops were then sent on to Washington, D.C. From D.C., it is likely that Nelson and the new draftees traveled to Virginia by steamboat to supply camps along the James River. The main supply point was City Point, VA where General Ulysses S. Grant had his headquarters. From there, the troops and supplies could go west by train to areas near the battlefield.

As mentioned in a previous post, my father often told a story about his grandfather Nelson shaking hands with Lincoln. It’s quite possible that Washington D.C. was where it happened. We know Lincoln was in D.C. at the end of January. January 31st was when the House of Representatives passed the resolution for the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery. Lincoln then signed the joint resolution of Congress on February 1st, sending it to the states for ratification. So it is possible Nelson shook hands with Lincoln during this time. At the very least, it’s likely Nelson was in or around D.C. for this historic moment.

But a chance meeting with Lincoln could have occurred later. Lincoln was in D.C. for most of February through his second inauguration on March 4th, which was attended by thousands of troops. States had until February 15th to fill their quota for the December 1864 draft call. So it is possible the replacements didn’t go to D.C. until after the 15th. But based on the records of other soldiers, it seems Nelson and the other new recruits were in Virginia by the first or second week of February. The Unit Record of the 94th shows that a John Fossett (28) enlisted into Nelson's same Company B in Watertown, 3 days after Nelson, and then died of smallpox on February 23rd in the Third Division's hospital at the V Corps encampment in Virginia.

Lincoln was also in Virginia multiple times. He took trips by steamer between D.C. and Virginia and could have been on the same boat as the replacement recruits. He was in Virginia on February 2nd and 3rd to discuss a possible peace treaty with confederate officials. Lincoln traveled there on a large steamer, the Thomas Collyer, with only his valet and one bodyguard. The large ship likely also carried replacement troops and supplies.

The Army of the Potomac in Virginia

At the time, the 94th NY Infantry Regiment and the rest of the Army of the Potomac were south of two Confederate cities, the Rebel capital Richmond, VA and the transport hub of Petersburg, VA. The Army of the Potomac, led by Major General George G Meade, was now made up of 3 Corps of 15-20,000 men each (II, V, and VI Corps). The 94th was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of the 3rd Division of V Corps.

The 94th Infantry’s activity and the exploits of the divisions and brigades of V Corps can be followed via the reports from and about their commanding officers. Military records, newspaper articles, and journals from soldiers provide us with many details about the generals and their armies and regiments.

We know that the 94th Infantry was in poor shape when Nelson joined the unit. The unit fought at Hatcher’s Run from February 5-7, where they suffered 40 casualties out of only 221 men that were fit enough to fight. Many more were mustered out of the unit in February, after their 3-year commitments were up. So the 115 new recruits who joined from January 25-31 along with Nelson became a large part of the regiment.

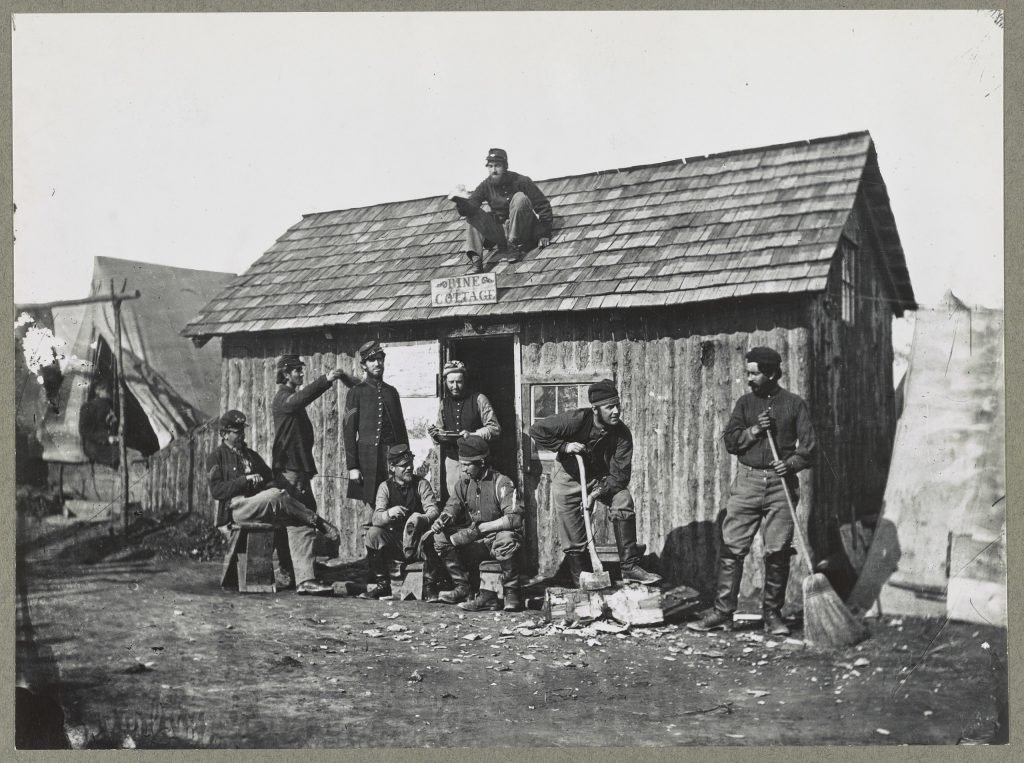

By March 1865 the 94th NY Infantry Regiment was down to 9 officers and 214 men, down from nearly 1,000 at its peak early in the war. The long winters, poor living conditions, limited medical care, and a smallpox epidemic all took their toll on the soldiers (by this time nearly 250,000 Union soldiers and 150,000 Rebels had died from disease alone). The Chaplain of the 94th Infantry, P.G. Cook, set the scene of the regiment’s status in February of 1865 as Nelson and other replacements joined it. His report published in the New York Reformer (Watertown, NY) is as follows:

“The late battle along “Hatcher’s Run,” will doubtless cause much anxiety among those having friends in the several regiments known to have participated in them….. Although the men were not…fortunate, the list of the wounded, among them being somewhat numerous, there are, comparatively, few cases of a serious nature. The men, however, suffered much from exposures to the severity of the weather.

The change from our comfortable winter quarters to the cold, rain and sleet which have prevailed in this vicinity. Since the movement was commenced there has been a severe draft upon the energies and probably a considerable drawback upon the efficiency of the army. It was simply impossible for the men to be in their usual fighting trim in such a storm as that of Tuesday. After exposure to intense cold of Sunday and Monday nights, the drenching rain and sleet of the following day were more than a match for their powers of endurance.

Our corps (the 5th) are still mostly in the vicinity of the “Rva” (Richmond, VA). Rumor hath it that we are to move up bag and baggage and hold the ground we have gained. If so we shall be obliged either to construct winter quarters for the third time, or live for the balance of the season in shelter tents.``

The Army of the Potomac Prepares for the Spring Campaign

The two armies were incapacitated by the rains in this swampy area around Petersburg, VA. An aide to General Meade, Col. Theodore Lyman, wrote to his wife on March 4, 1865 that he didn’t anticipate them seeing any action until April 1st due to the conditions:

“to-day we are favored by a persistent northeast rain… You would not give us much credit for a chance to move, could you see the country; the ground everywhere saturated and rotten, and giving precarious tenure even to single horses, or waggons.”

General Grant at this point thought the war might continue for another year, especially if the Rebel’s General Lee could move to the west of Grant’s lines and escape to the south. The Confederate government had extended conscription in 1864 to all men from age 17 to 50 and more recently created a junior reserves of boys 14 to 16 and a senior reserves of 50 to 65. Though under-manned, Lee’s generals and troops were still capable.

Grant had decided to wait for the rains to subside and for his cavalry to arrive from northeastern Virginia. Cavalry would be essential in moving quickly to block Lee’s escape, however, the swollen creeks and rivers were blocking cavalry movements. In the meantime, Grant issued an order to the Army of the Potomac on March 1st to be ready to move at a moment’s notice.

Meanwhile, General Lee at his Petersburg headquarters was making plans as well. His Army of Northern Virginia was only half the size of Grant’s assembled forces. Lee’s food supplies were low and every day his army was shrinking with desertions. He asked one of his generals for options and advice. The general’s ideas were: 1) offer peace terms to the Union Army, 2) retreat from Petersburg and their capital, Richmond, to link up with other southern armies, 3) attack as soon as possible.

In the next post, we will see what choices Lee and Grant made in the last battles of the Civil War. We shall also learn where my Great Grandfather Nelson and President Lincoln definitively came in contact.