My father loved telling stories about our family whenever visitors came for dinner or a card game. Typically, visitors would sit facing two photos of men on the wall, one young and one old. Both lives faced great upheavals, one whose life was fortunate while the other’s was tragic. The portraits of these two are so attractively done that invariably someone would ask about one or the other.

The tragic tale invariably came first, as the portrait of my mother’s handsome and youthful looking father naturally draws in the viewer. My grandpa E.T. was a 25-year-old motorcycle officer who was shot and killed during a traffic stop in Alabama just months before my mother was born.

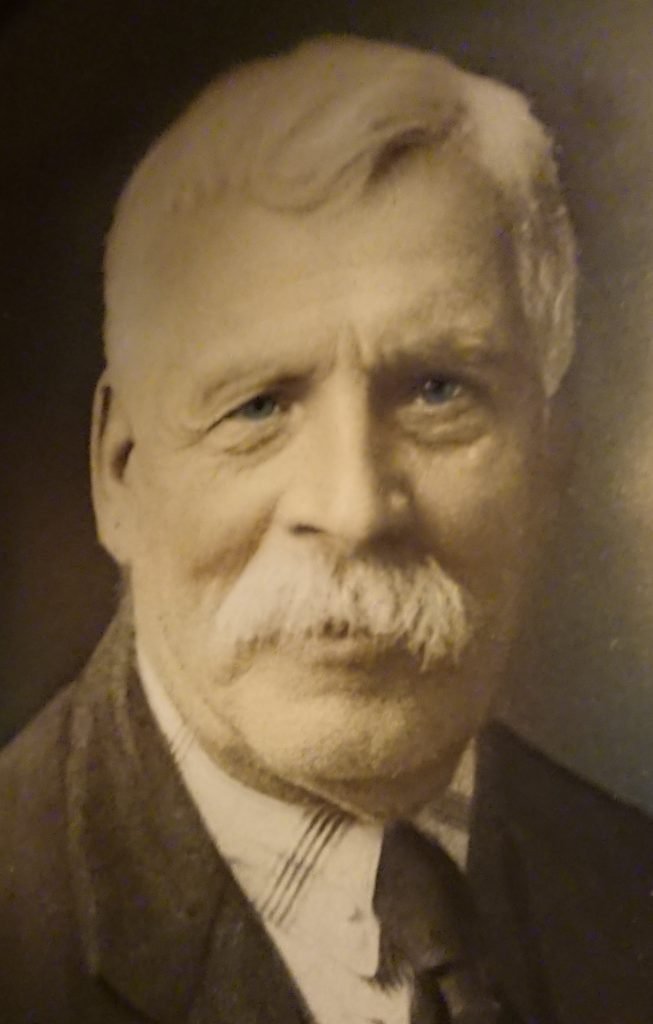

It’s hard to come up with much to say when hearing about such a tragedy. After a moment of silence, my father would then re-direct attention to the portrait that offered a happier tale, the photo of my grey-haired great grandfather.

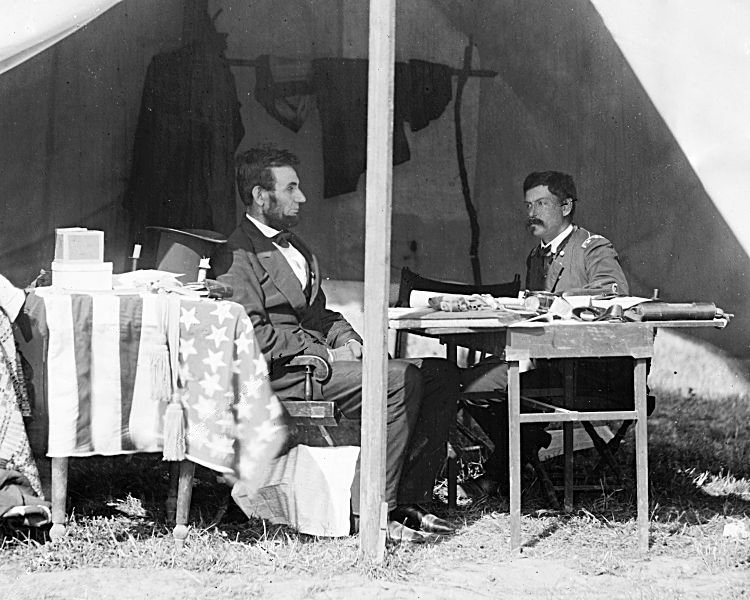

My father would explain that the man was his grandfather Nelson who was in the Civil War. Then he would mention that through some fortunate turn of events during the war, his grandfather shook hands with Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln reportedly even remarked that this young man “should be back home on the farm.”

This tale of a brush with such an icon from history seemed a source of great pride for my father to tell. My father was only 5 when my great-grandfather died, so I doubt he ever heard the story directly from the source. Most likely, it was a story he heard from his father.

As someone who loves history, I was curious where and when this chance meeting might have occurred. Ancestry has so many good links to databases and the Civil War is so well catalogued online, that it was easy to track down some details of Nelson’s life.

Where was My Great Grandfather in 1865?

A curious thing about Nelson is that he was Canadian, born and raised in a small town just across the New York side of the St. Lawrence River. I originally thought he was born on the U.S. side of the border, but US and Canadian census rolls all list him as being born in Canada.

To crack the mystery of how and where he might have met Lincoln required some digging into the history of his outfit in the Army of the Potomac. Fortunately, the New York State Military Museum provides a detailed collection of records about Nelson’s war record that sheds light on this era. His unit’s roster tells us that he (listed as “Nelson Hughs”) served in the U.S. Civil War for a brief 6 months in 1865, beginning in January 1865.

Where was Lincoln in 1865?

Nelson's brief record of service immediately gave me some doubts as to the truth of the Lincoln handshake story. It occurred to me that if my grandfather was the one who told this war story to my father, he might be a somewhat unreliable source. My grandfather was a hardworking man who provided well for his family, but he was an alcoholic. So I could imagine my grandpa burnishing a tale about his father while under the influence. But my great-grandparents also had 8 other children who all lived in the same area along both sides of the St. Croix River. It is likely any story about Honest Abe was told widely amongst the aunts and uncles at family gatherings and became part of family lore.

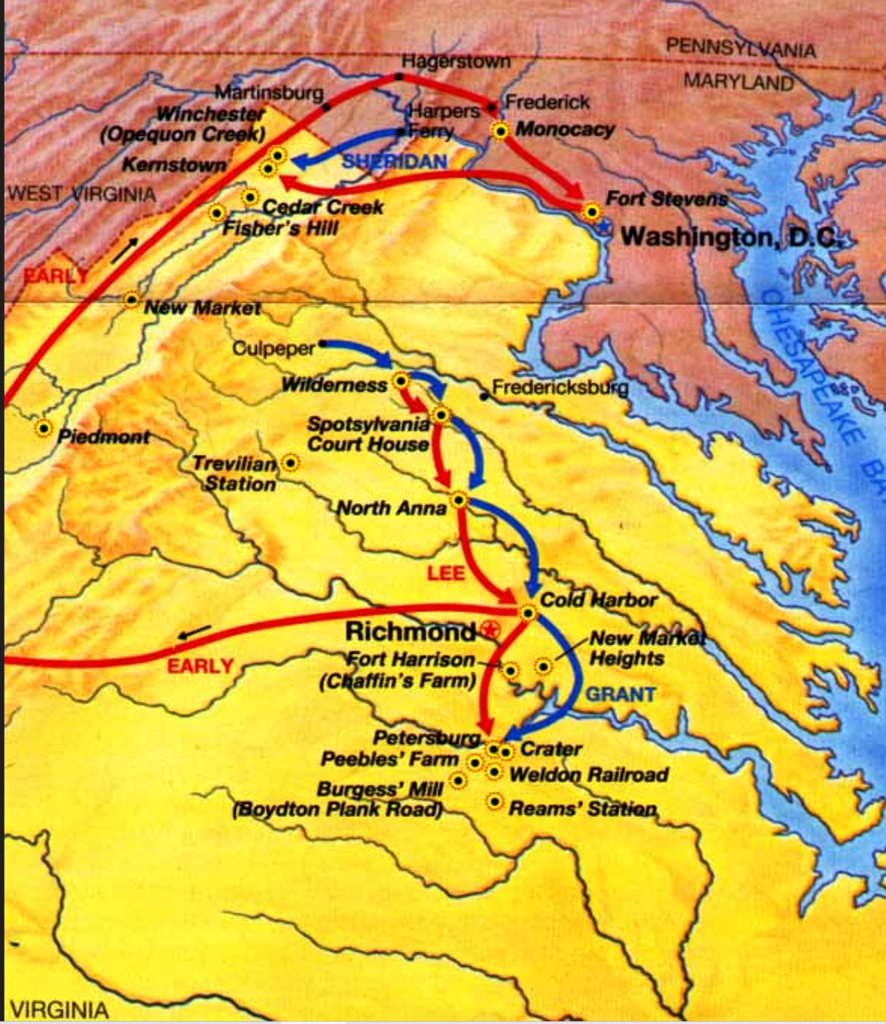

So I looked at anything I could find that could tie the two together. I looked at where Nelson was in various battles and I researched into what Lincoln’s movements were during that time. There are several accounts of Lincoln meeting with or addressing troops. The deeper that I looked into my great-grandfather’s service record and the location of his unit, a chance meeting with Lincoln seemed possible.

What is surprising about Nelson’s record is that, in that short period of time, he took part in some of the most consequential battles of the war. In fact, he not only witnessed the surrender of the South’s greatest army, but he marched in the victory celebration along Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.

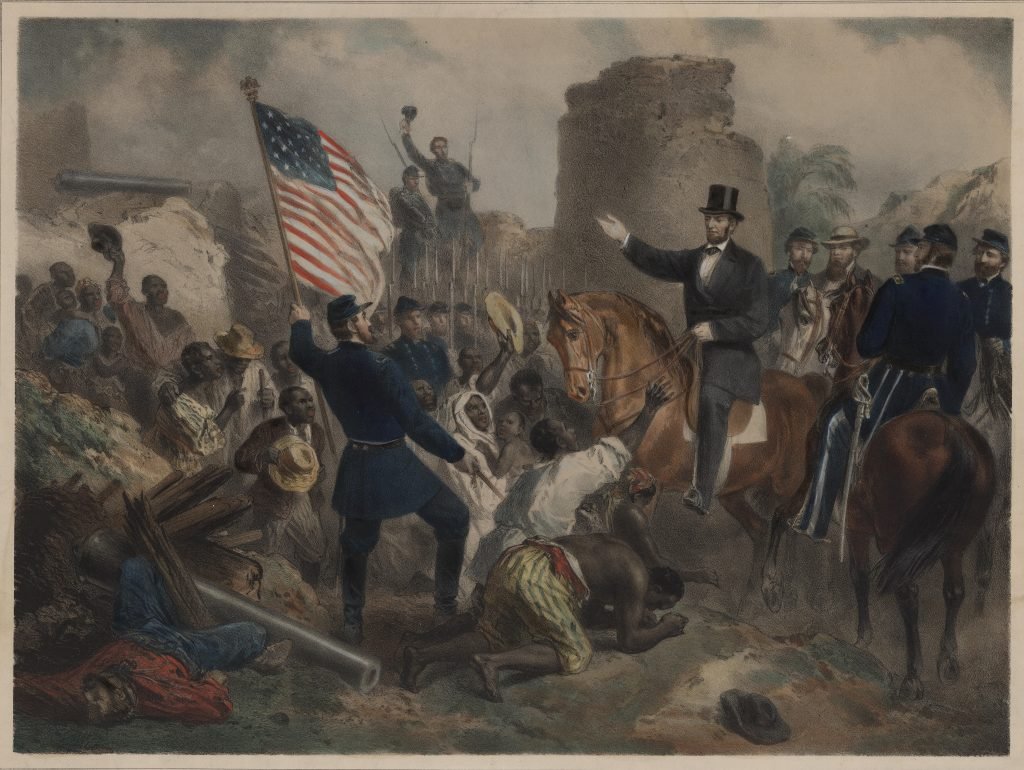

John Wilkes-Booth assassinated Lincoln just days after the Union victory in April 1865. But prior to this, Lincoln spent a lot of time in proximity to the battlefields in Virginia where the Union defeated the Army of Northern Virginia. During that time, it is quite possible that Nelson saw or shook hands with Lincoln, one of the greatest commanders-in-chief in US history.

Background on Nelson’s Unit, The 94th NY Infantry Regiment

To tell this tale of Nelson’s brush with some of the war’s major icons, I’ll first provide some background on his unit. We’ll look at the unit’s origins and organization. Then, in a second post, I will relate the dramatic series of battles that brought Nelson into proximity with Lincoln and some of the war’s greatest generals on both sides.

Nelson was part of the 94th New York Infantry Regiment (also known as the “94th NY Volunteers,” "Bell Rifles," or "Bell Jefferson Rifles"), a unit of volunteers organized in Jefferson County, New York, near the banks of Lake Ontario. The army formed the unit on March 10th of 1862 in Sackett’s Harbor, N.Y. The men of the 94th were mustered into the Army on a 3 year enlistment. They were all volunteers since the US didn’t institute a draft until March 1863. Many early volunteers were generally eager, thinking that victory would be easy. But as casualties mounted, states and counties offered bounties in order to recruit soldiers, with rates that began at $100 and went up as high as $1500.

Around this time, Nelson was 16 and working as a laborer 100 miles away from Sackett’s Harbor, in Williamsburg, Ontario. He was living on the farm of John D. Loucks. Loucks was married to Catherine Rombough, likely a cousin of Nelson’s mother, Elsie Jane Rombough. The Rombough family had originally immigrated to New York from Germany in the mid 1700s, but relocated to Canada after the Revolutionary War. So Nelson likely had some understanding of New York passed down through his relatives.

As the Civil War progressed, the Union Army casualties mounted. By war’s end, the combined casualties of the two armies would total over 655,000 dead and 475,000 wounded. Thanks to populous states like New York, the Union had a numerical advantage over the less populous South and were able to replenish units on a regular basis. Units like the 94th N.Y. Volunteers would add soldiers throughout the war. Over time they added five more companies to bring the regimental strength up to about 1000 men by 1863.

Battlefield Training

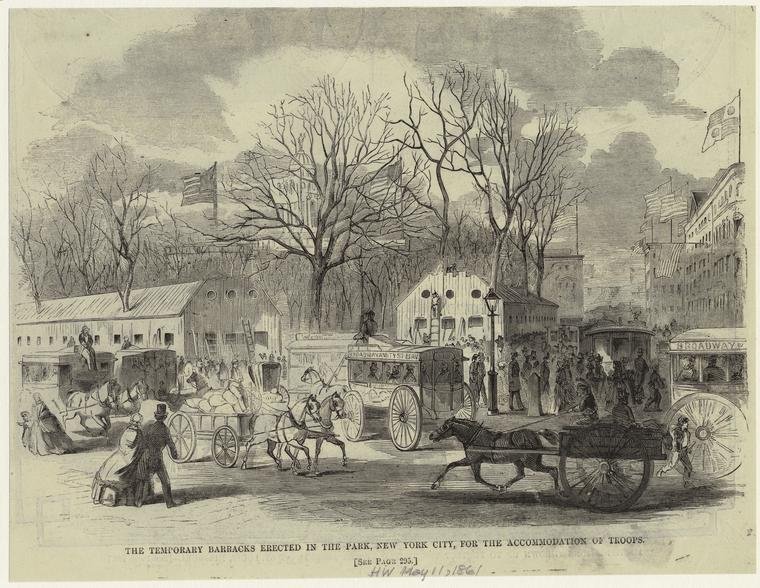

Like all Union Army units in those times, the 94th received little more than basic weapons training and were sent off by train to Washington, D.C. on March 18th. Their luck wasn’t good from the start, as their train from Watertown, NY to Washington derailed, killing several soldiers. The regiment lost most of its equipment in the crash and had to be resupplied in New York City at the temporary barracks set up in the park next to city hall. From there they traveled to Washington D.C. and then across the Potomac River to Fort Lyon, VA to join the defense of D.C.

The main training the officers and soldiers had was live action on the battlefield, as few officers on either side had any experience with managing large units. The confederate army had the benefit of having officers, like General Robert E. Lee (the 2nd commander of the Army of Northern Virginia). Many of them were veterans of the Mexican-American War, the Seminoles War, and other battles. Lee was a top graduate of the U.S. military academy, West Point and later held the academy’s highest office, commandant. This wealth of experienced generals in the confederate army led to many of their early successes.

The 94th NY Infantry saw many battles and challenges during its first 2 years of service. In August 1862, they saw their first major engagement in Virginia, where they suffered 147 casualties (37 dead and the rest wounded or missing). This 15% depletion of their fighting strength meant they needed a continual replacement of men, especially after other major battles in Virginia and Gettysburg, PA, where they had 245 casualties (166 of whom went missing).

Conscription Act of 1863 Setting the Stage for Nelson’s Enlistment

Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1863 to replace the casualties and build up the ranks before the 3 year enlistments were up. The act required registration by every male citizen and immigrant who had applied for citizenship between the ages of 20 and 45. They drew names from the draft list in every town to fill each town’s quota. However, there were some exceptions for certain family situations. And there was also an option to pay a $300 exception fee to get out of serving, or a draftee could hire someone to take his place.

It was this latter exception that brought Nelson, a Canadian living in Canada, to enlist in the 94th New York Infantry. He might have learned of this way for Canadians to enter the war from his 3rd cousin, Nelson B. Rombough, who joined the 2nd Regiment of the New York Heavy Artillery in December 1863 at age 34. This Nelson also only saw 6 months of active service, as he was wounded in May 1864, in the Battle of Spotsylvania (where 30,000 men were killed, wounded, or captured). Nelson B. was discharged from the army in February 1865 with a disability from those injuries, just after our Nelson enlisted.

It’s unclear when Nelson would have made it to the Union lines where his unit was. At the time they were on the front line south of Petersburg, VA. It is likely Nelson made it there from the middle to late February, a time just following a major battle the unit fought in called Hatcher’s Run (February 5-7,1865).

In January and February of 1865 the 94th NY Regiment roster shows many veteran soldiers received their release from the Army during this time, while dozens more new recruits were added. So it could have been in March that the unit fully returned to action for the next stage of the Siege of Petersburg. The next record of casualties in the 94th did not come until the Appomattox campaign that ran from the end of March through early April 1865.

The Siege of Petersburg

The siege of Petersburg was a plan of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to encircle Petersburg, VA and block off supplies to Robert E. Lee’s army. The 94th Regiment was there from the beginning of the siege. In the early summer of 1864, the 94th traveled south from positions northeast of Richmond to the James River. From there they traveled by boat across the James River, landing at a position just east of Petersburg.

A soldier from the 94th NY Infantry, “C.W.S.,” related this June 1964 journey to Petersburg in a letter to a newspaper near Watertown, NY, The Northern Journal. It was the beginning of what would become an 8th month struggle now known as the Petersburg Campaign.

“We left Cold Harbor (Virginia) on the 11th June, leading another flank movement, and halted for the night three miles from the Chickshominy. The next morning, at grey dawn we moved down to the river and crossed at Long Bridge. We found it awful cold; also the cavalry skirmishing with the rebels in the background.

The country south of the Chickahominy is rolling, and is interspersed with quite pleasant farm houses, and pine and white oak timber land. The cavalry kep the rebels moving, so that our march in following was quite a lively match. Our division leading and Gen. Crawford commanding, and our regiment led the division. Three miles from the river our ears were suddenly saluted y the boom of a cannon, and we soon found that the cavalry had met something more than pickets. Our brigade, Col. Bates commanding, was sent forward to support, and found that the enemy were in some force in White Oak swamp, and were shelling us vigorously from one of McClelan’s old forts. The 94th advanced under a heavy fire to relieve the cavalry, who were having hard work holding back the rapidly arriving “Greys.” We were deployed as skirmishers, a company at a time, and sent into the swamp. We received a galling fire in going over the hill, losing 8 killed and 12 wounded. Here we held them till night, watching them throw up works, in expectation of a visit from the Army of the Potomac….at night we were quietly withdrawn to follow the army, which had passed in rear of us during the day, across the James River.

We took the “Express” and was passed through to Petersburgh, not stopping even to the authorized places for refreshments. Arriving on the 16th of June, we found the 9th Corps fighting as usual, having taken during the day a line of pits and some forts from the enemy. Our corps laid still all the 17th, as we generally do, after running our legs off to a place. In the evening we helped part of the 9th Corps to make a noise and take another lot of pits, our part consisted of making the noise. The next morning we made and advance of one mile, and found nothing but skirmishers to repel it. We occupied the Norfold & Petersburg Rail Road, under fire of shell and canister from rebel guns on a hill fifty rods beyon. During the night they had thrown up heavy works, and we found it necessary to halt under the protecting care of the railroad banks.”

The State of the War in Virginia, January 1865

The siege of Petersburg did not accomplish a complete encirclement of the city. The Union troops caught the Rebels by surprise. But the Union generals first on the scene in June 1864 hesitated too long and confederate reinforcements were able to hold off the federal troops. Eight long and bloody months ensued as the Union gradually extended the Confederate troops lines further west, in order to take advantage of the Union’s superior numbers.

In the final 6 months of 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman moved across the south from Tennessee, through Alabama and Georgia to Atlanta and Savannah on the coast of the Atlantic. His march destroyed the southern arms factories and infrastructure. His campaign also limited the number of reinforcements that could reach Virginia.

The siege in Virginia and “Sherman’s March to the Sea” set the stage for the final battles that would win the war for the Union. In the next edition, we will look at Nelson’s entry into the war and follow the battles through the media reports that mention his commanders.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.

Tom,

This is great work. I anxiously await your future installments. I know my mom would love it too! I remember going with her to the Huntington Beach Library to review census records on microfiche. The internet resources available now make this kind of research a whole new ballgame…

Dan