On the March with V Corps of The Army of the Potomac

The morale of General Samuel Crawford’s 3rd Division must have been very high in the last week of March 1865. The division had just been reviewed by their Commander-in-Chief Abraham Lincoln, his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, and their commander of The Army of the Potomac, General George Meade. But their opponent, the Army of Northern Virginia and its commander, General Robert E. Lee, were still actively resisting the Union assault on Petersburg.

After the Confederate’s March 25th attack at Fort Stedman failed, General Lee sensed the Union would look to go around his right flank and surround his army. To block the Union forces, Lee moved several divisions of infantry and cavalry to White Oak Road and the intersection of Five Forks. These troops would protect the roads running through Five Forks. They were also essential to help hold the South Side Railroad line to Petersburg and the Richmond-Danville Railroad further north. If Lee could not hold these last supply lines, there would be no way to hold Petersburg or Richmond, the capital of the Confederate States of America.

The day before Lee’s attack, the Union’s overall commander, General Ulysses S. Grant, had issued orders for Union troops to move westward on March 29th. Two days before this movement, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, General George Meade, met with the generals commanding his key Army Corps: General Humphreys of II Corps, General Warren of V Corps, and General Wright of VI Corps.

The Beginning of the Appomattox Campaign

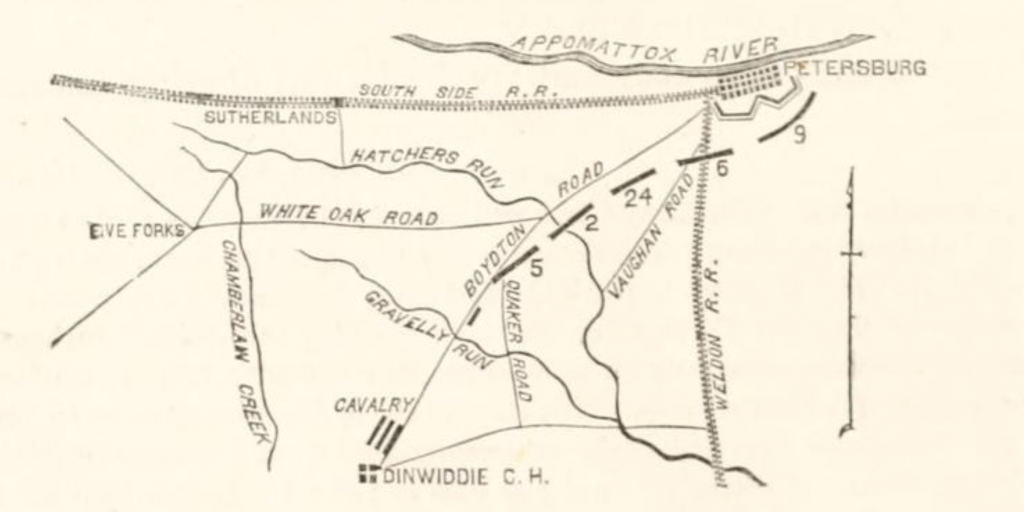

The action began at 3 a.m. on March 29th for my great grandfather Nelson Hughes, his 94th New York Infantry Regiment, and the rest of his comrades in 3rd Division and V Corps. Units from General Ord’s Army of the James had moved in the day before to take the V Corps position on the lines near Hatcher’s Run, which had been captured in February. Also moving west was the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Shenandoah, led by General Philip Sheridan.

The 15,500 men in the 3 divisions of V Corps marched southwest down Vaughan Road, then headed west on Old Stage Road. Before departure, the men had been warned that any man dropping out of line without permission from the division commander could be shot. They were also told to travel as lightly as possible, so that they were prepared to fight at a moment’s notice. Among the things left behind was the V Corps’ band.

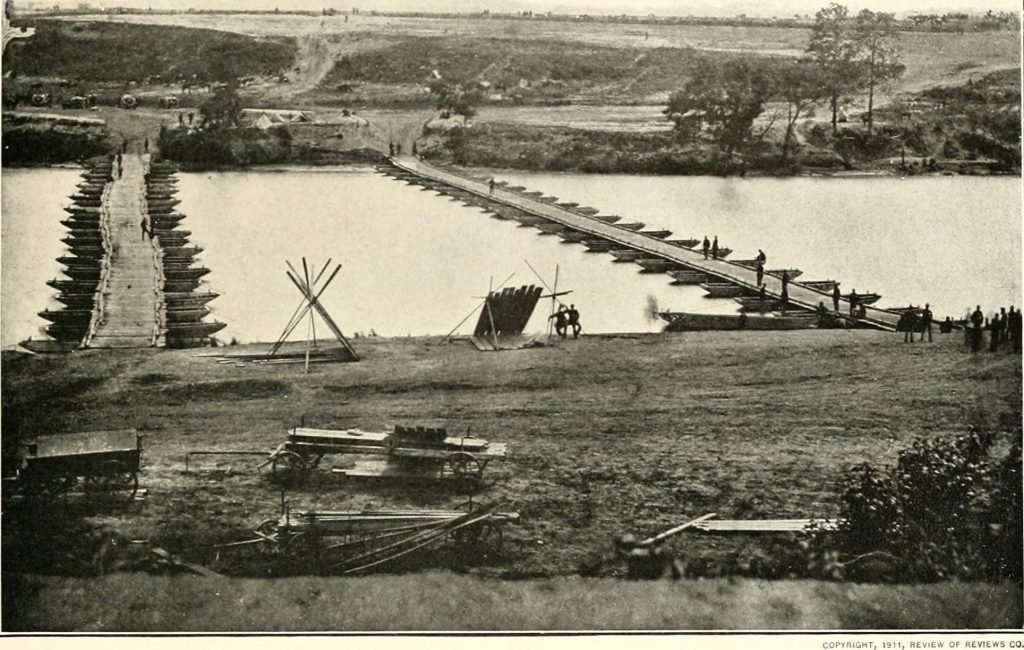

At some point, the column had to use a pontoon bridge to cross Rowanty Creek. Then they headed up Quaker Road to Boydton Plank Road, one of the main supply routes to Petersburg. Along the way, they encountered small Confederate pickets (checkpoints) made up of cavalry troops. They also had to wade through another creek where the Rebels had destroyed a bridge.

General Chamberlin, commander of 1st Division, described the conditions the Union troops faced:

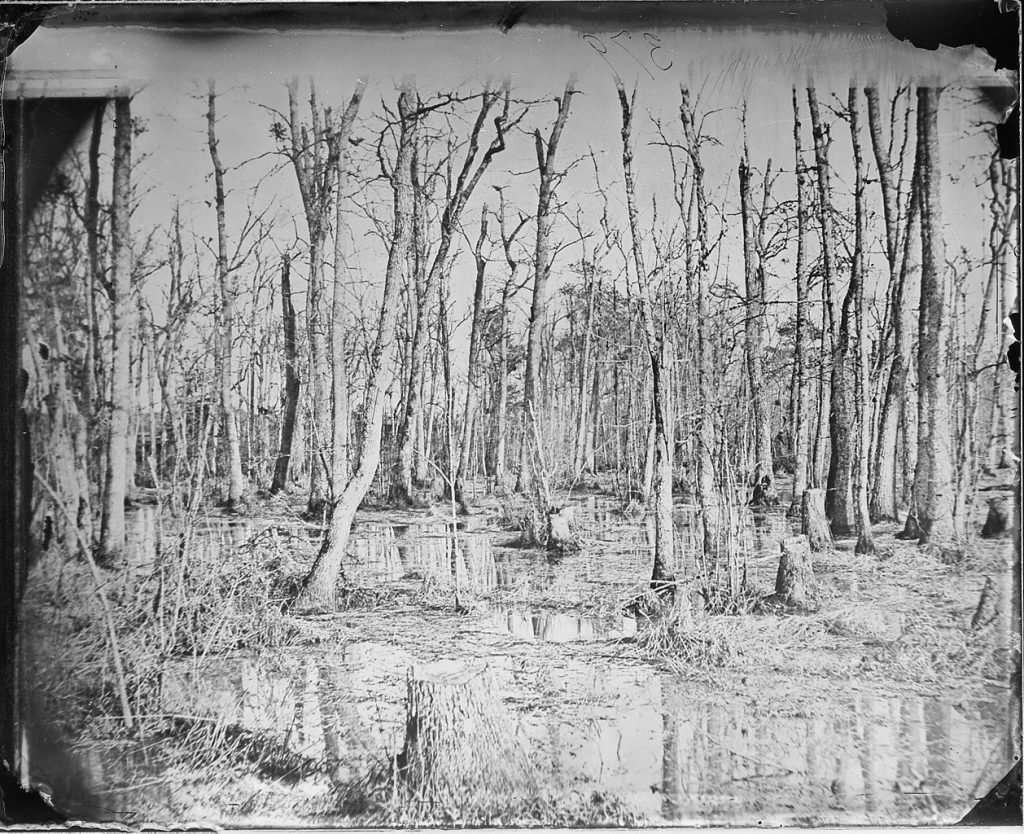

“The ground about to be traversed by us is flat and swampy, and cut up by sluggish streams, which, after every rain, become nearly impassable. The soil is a mixture of clay and sand, quite apt in wet weather to take the character of sticky mire or of quicksands. The principal roads for heavy travel have to be corduroyed (a road of logs) or overlaid with plank.”

Lt. Colonel Horace Porter, an aide to supreme commander General Ulysses S. Grant, described the conditions in biblical terms:

“The country was densely wooded, and the ground swampy,… whole fields had become beds of quicksand in which horses sank to their bellies, wagons threatened to disappear altogether, and it seemed as if the bottom had fallen out of the roads… The roads had become sheets of water; and it looked as if the saving of that army would require the services, not of a Grant, but of a Noah.”

The rains would fall so heavily that, by the next day, Rowanty Creek would widen such that the pontoon bridge was too short. This would hold up the wagons carrying supplies and needed equipment, such as the shovels and tools V Corps would need to dig trenches. The wagon trains wouldn't resume until the afternoon of March 31st.

March 29, 1865 - The Battle of Lewis Farm

V Corps and the Cavalry Corps were on the far left end of the Union Army’s lines. The plan was to flank the Rebels’ right side and cut off any route of escape from Petersburg for the tens of thousands of Rebels still there. At some point in the morning of the 29th, the Confederate Army detected the Union’s movements and General Lee sent units to block their advance. The 1st Brigade of V Corps’ 1st Division was at the front of the column and encountered 3 brigades of Rebels at Lewis’ Farm on Quaker Road.

During a two-hour battle, the 1st Division suffered 367 casualties, with most from the 185th New York Infantry Regiment in the 1st Brigade, which had 55 killed and 148 wounded. The commander of 1st Division, General Joshua Chamberlain, was also wounded, but V Corps managed to force the Rebels to withdraw to White Oak Road.

After the Union troops settled into positions along Boydton Plank Road. Heavy rains fell on the evening of March 29th and into the 30th, making movement in the sandy, swampy soil difficult for the advancing troops. Small units from V Corps were sent out to find the Confederate positions. V Corps saw only brief engagements with the Rebels, though troops from the Army of the James attacked further east of the V Corps front in an attempt to break through the thinning Confederate lines.

Two divisions of V Corps moved off of Boydton Plank Road on the afternoon of the 30th, with General Ayers’ 2nd Division taking the lead position, moving within a half mile of White Oak Road. The Confederates had trenches along White Oak Road, but visibility was difficult in the rain and fog. Behind Ayers was General Samuel Crawford, leading the 3rd Division, which included my great-grandfather Nelson’s 94th NY Infantry. General Griffin’s 1st Division moved off of Boydton Plank Road to be close enough to support the 2nd and 3rd Divisions. Meanwhile, late at night, a division led by General Miles from II Corps moved up to take up positions further up Boydton Plank Road.

White Oak Road was a key artery running East-West from Petersburg before bending towards the southwest. It would be a key escape route for the Confederate Army if it hoped to flee to North Carolina, where Confederate General Joseph Johnson’s Army of Tennessee was still fighting. The road was also a mere 2-3 miles south of the Rebel held South Side Railroad. The important Five Forks intersection was 4 miles to the west of the Union positions.

Control of Five Forks would provide two more roads from which to attack the Confederate rail lines as well as routes to interdict Rebel troops fleeing on foot. And White Oak Road would provide the shortest route to Five Oaks. If V Corps could take White Oak Road, they could link up with General Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps for a two-pronged assault on Five Forks. Sheridan had the opportunity to take Five Forks when it was protected by only a small force on the 29th and 30th, but he paused and allowed the Rebels to reinforce the troops there and build up defensive barriers and trenches.

March 31, 1865 - The Battle of White Oak Road

March 31st dawned with Union commanders preparing for an attack on White Oak Road. But as the rains continued into the morning, at 8:30 a.m. the Union commanders at Army of the Potomac headquarters decided to halt operations for the day. Some V Corps regiments began to relax at this news. At 10 a.m. the sun appeared and some troops in Griffin’s 1st Division in the rear took out their blankets and clothing to dry in the sun.

General Ayers’ 2nd division was roughly 600 yards south of White Oak Road. To assess whether the Rebels might attack, V Corps’ General Warren had Ayers move up for reconnaissance of the Rebel’s front line strength. If Rebel strength was weak, V Corps had permission from General George Meade (Commander, Army of the Potomac) to take out the Rebels’ position. General Chamberlin of the 1st Division shared the mood of the commanders and men:

“Wet and worn and famished as all were, we were alive to the thought that promptness and vigor of action would at all events determine the conditions and chances of the campaign.”

But as Ayers’ men crept through the woods to within 50 yards of the road, the Rebels attacked from two directions. General Robert E. Lee had personally inspected Rebel lines on White Oak Road that morning, and ordered two brigades of his troops to attack on the Union’s flank. Rather than serving as overall commander, Lee was in direct command of over 11,000 Rebel troops on that stretch of White Oak Road that day.

Ayers’ troops were poorly positioned for the Rebels’ attack and were quickly overwhelmed. They fell back into and through General Crawford’s lines (and those of the 94th New York Infantry). The disruption of 3rd Division’s lines eventually caused those men to pull back as well, but not before suffering several casualties, including Major Henry Fish, the 94th NY Infantry’s commander, receiving a wound to the head. However, Fish remained with his troops, despite the protestations of his officers.

The melee from the Rebel attack caused General Griffin’s division in the rear to abandon their laundry and form lines to face the oncoming Rebels. With Griffin’s men on a rise above a creek, the Rebels’ attack was slowed as they attempted to cross the water that was waist-deep. With the Rebels stalled, Griffin’s troops pushed forward in a frontal attack. The 2nd & 3rd Divisions of V Corps then re-formed their lines to support 1st Division. Further to the right, II Corps attacked the Confederate soldiers in front of them from their positions on the northern section of Boydton Plank Road. This broad counterattack caused the 4500-5000 Rebels who attacked to withdraw.

In the afternoon, both General Grant and General Meade observed the fighting from where the 1st Division had camped the night before. By now, 1st Division was pushing forward to White Oak Road and its 1st Brigade crossed it forcefully, taking the trenches previously occupied by the Confederate’s 56th Virginia Infantry. Lieutenant Evan Morrison Woodward (a Medal of Honor recipient) recalled the crossing:

“The moment the First Brigade came into full view a terrific fire of the enemy converging from the front, and right and left, with their artillery at close range, made it a blinding storm of destruction in an instant…On they dashed, every color flying, officers leading, right in among the enemy, leaping the breastworks, a confused struggle of firing, thrusting, cutting, a tremendous surge of force, both moral and physical, on the enemy’s breaking lines, and the works were carried.”

After nearly 3 hours of fighting, at dusk the Union troops set up positions along the road and in the Rebels’ former positions, facing the remaining Confederate troops on their right. At the cost of over 1400 casualties, the V Corps had captured a section of White Oak Road, splitting the communication and supply lines between the Rebels at Petersburg and those defending Five Forks. And the progress made had been done entirely with muskets and bayonets as most of the V Corps artillery was stuck on Boydton Plank Road due to the mud and thick forest.

But there were concerns in the west. General Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps had been driven back along Dinwiddie Courthouse Road, the southern approach of Five Forks. Confederate General Pickett’s infantry and General Fitz Lee’s cavalry had beaten back Sheridan’s advance and divided his forces. From White Oak Road, the V Corps commanders could hear the fighting going on at Dinwiddie. Concerned about a Rebel attack from their rear, General Warren sent a brigade off towards Dinwiddie to recon the enemy’s positions and provide support for Sheridan.

On White Oak Road, the Rebels had pulled back behind their barriers to the right of the section Union troops had captured. General Chamberlain described his reconnaissance of the Rebel lines with General Warren:

“Just after sunset Warren came out again, and we crept on our hands and knees out to our extreme picket within two hundred yards of the enemy’s works, near the angle of the Claiborne Road. There was some stir on our picket line, and the enemy opened with musketry and artillery, which gave us all the information we wanted. That salient was well fortified.”

The V Corps troops held the positions in front of them while generals traded messages and orders between three different headquarters and Dinwiddie Court House. At the separate headquarters of General Grant and General Meade, there was some confusion about what to do next. Part of the issue was that earlier in the week Grant had promised General Sheridan an infantry corps for his push up north to block the Rebels’ South Side Railroad. The closest one to him was V Corps. In the early evening, General Meade sent out an order for V Corps to entrench their lines for possible attack the next day and mentioned that V Corps (after 3 days of marching and fighting, on limited rations in the rain) would make no attack on April 1.

But the Supreme Commander of Union forces, General Grant, had different ideas. At 9 p.m. Grant sent orders for V Corps to send a division to aid Sheridan at Dinwiddie. Somehow the officers at Meade’s headquarters had little understanding of V Corps’ position, for soon after this order, Meade directed that 1st Division should be sent, not 2nd or 3rd Division, who were on the opposite side of White Oak Road from the Rebels.

At that time, the 1st Division of V Corps had crossed White Oak Road and was only a couple hundred yards from the Claiborne Road intersection that ran straight to the South Side Railroad lines. Meade’s headquarters ordered General Griffin’s 1st Division to pull back from their position on White Oak Road and march 6 miles in the dark to support Sheridan at Dinwiddie. Then at 10:30 p.m. the entire V Corps was ordered to withdraw and head west using 3 different routes.

V Corps’ General Warren and his troops were naturally hesitant to give up the ground gained that day, but the Rebel troops pushing the Union’s Cavalry Corps down Dinwiddie Courthouse Road could, theoretically, threaten V Corps from behind. The Rebel troops at Dinwiddie could also degrade the valuable and mobile Cavalry Corps that would be needed to chase General Lee during his retreat. But rather than withdraw Sheridan’s more mobile force to support V Corps where they were dug in, Grant ordered the now 13,500 able-bodied men in V Corps to uproot, without wagons, rations, or hospital caravans to a new front 6 miles away.

Pulling out from White Oak Road

General Warren responded by first sending those closest to Dinwiddie, General Ayers’ 2nd Division. Ayers was dispatched to support Sheridan, but along the way they had to repair a 40 foot span of bridge at Gravelly Run (river), which delayed their movement.

Past midnight the 94th NY Infantry and the rest of the front-line V Corps troops were summoned one by one (rather than by bugle call), so as not to alert the Rebels of the Union troops’ movements.

General Griffin’s troops were the furthest forward units, having captured the opposite side of White Oak Road. They finally disengaged from their positions around 4 a.m. and headed west at 5 a.m. on the White Oak Road. Then they turned southwest on Crump Road towards Dinwiddie, wading through a river along the way.

General Crawford’s 3rd Division then pulled out from their positions facing across from the Rebel’s headquarters on White Oak Road. They were further down White Oak Road, to the right of where 1st Division had been. My great-grandfather’s brigade commander, General Coulter, reported that his troops spent the stormy night laying on their muskets, doing without tents or camp fires given the proximity of the Rebels across the road. They pulled out cautiously, as the rear guard for the V Corps, prepared to fire on any Rebels that attacked.

After getting clear of the front lines, 3rd Division followed the 1st Division down White Oak Road. They marched 6 miles southwest towards Dinwiddie and then north to a rally point southeast of Five Forks. Perhaps due to fatigue (or temporary insanity from the crazy orders), several men from the 94th deserted during the march or were lost in the woods during the withdrawal, including 2 from my great-grandfather Nelson’s B Company.

What awaited them at Dinwiddie and Five Forks on April 1, 1865? It would be nothing less than the most important battle of the year. We will pick up there in our next edition.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.